Why We’re Willing to Pay for Certainty

Hello Readers,

While looking for ideas this week, I stumbled over this headline that caught me off guard: Gen Z-focused startup Slikk raised $300,000 to offer 60-minute clothes delivery. Sixty minutes! For clothes!

I guess it's hardly surprising that a firm offering quick fashion is generating headlines and drawing investors in a world where patience is as archaic as dial-up internet. But it also made me wonder about what drives this fixation? It’s not just about getting things fast now, but about the certainty that they’ll arrive exactly when promised. So, what happens when those promises fall short?

While the need for certainty and speed isn't new, the rise of digital technologies has amplified it. Businesses today feel under pressure to offer real-time data on everything, from how quickly your pizza gets to your door to the speed of a container ship carrying your new automobile over the ocean. This move towards certainty has affected how companies run and often forces them to promise more than they can deliver. And this is where the “extreme certainty trap” comes in. Mr. Ram Prasad, the founder of Final Mile Consulting, recently made the observation that businesses are becoming more and more caught up in the loop of providing greater certainty than they can actually provide. Consider ridesharing apps informing you your ride is "just seconds away," while in fact you can still be standing there five minutes later. It is not the waiting that is frustrating; rather, it is the shattered promise of certainty.

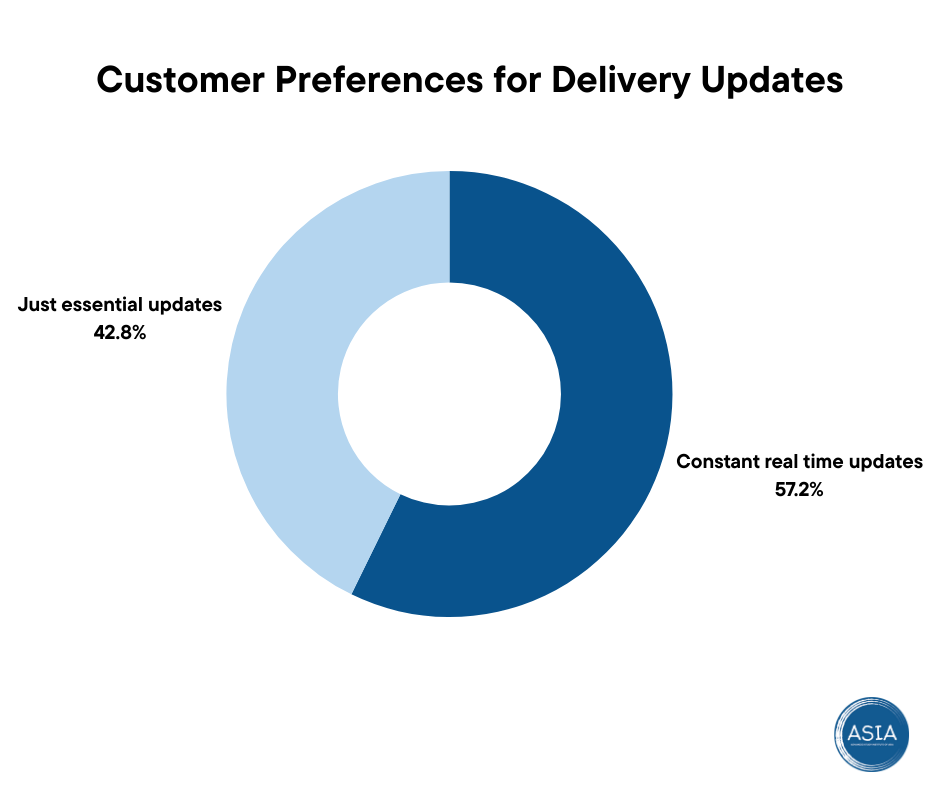

To delve deeper, I recently ran two social media polls to determine what consumers really want from delivery services. 57.2% of respondents in Poll 1 said they liked regular updates—tracking their order from the warehouse to their door at every level. In Poll 2, however, 71.4% of respondents said their delivery predictions of these services are often unreliable.

There are two essential takeaways from this:

One is that we like certainty in our services and are willing to pay for it.

Second is that we are irritated more by the uncertain delivery than the speed of delivery. Unfulfilled promises hurt more.

This is consistent with Prospect Theory, which suggests that individuals are more sensitive to losses—like unfulfilled delivery promises—than they are to profits, so uncertainty is more unpleasant than delayed, but consistent, service.

This so-called certainty trap is also not limited to consumer behaviour; it touches almost every aspect of our lives, including politics. Dr. Ilana Redstone, PhD, sociologist and professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign illustrates the ways that desire for certainty impacts sociopolitical discussions. In her work, she describes a concept Settled Question Fallacy, referring to the way people approach otherwise fluid and intricate issues such as race, gender, or politics, as if they are easily solvable, with rather clear cut solutions. She points out that this craving for certainty is something the late David Foster Wallace – an American writer and cultural critic had pointed out in his highly popular commencement speech at Kenyon College. One of the biggest issues Wallace pointed out was that of ‘blind certainty’ he suggested made people stick to their preconceived notions and failed to allow for the existence.

"A huge percentage of the stuff that I tend to be automatically certain of is, it turns out, totally wrong and deluded. Here is just one example of the total wrongness of something I tend to be automatically sure of: everything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the absolute center of the universe; the realist, most vivid and important person in existence."

He illustrates this with the story of these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says "Morning, boys. How's the water?" And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes "What the hell is water?"

Wallace’s point was clear: certainty is apparently an excellent thing but like everything in excess it can become a prison; our minds become confined, and we are unable to examine other perspectives.

Thus, the question arises and there seems to be no obvious answer as to , how one can escape from this loophole in the age of digital media?

Curiosity as one study done by Dr. Mark Leary, a social psychologist at Duke University shows that, people who can admit when they are wrong, or in other words those who are intellectually humble, always make better decisions, have better relations and are happier people. Dr. Leary’s works detailed that individuals, who accept vulnerability and venture into unknown, have higher chances, in comparison to those who limit themselves to closed-minded approach, in terms of relationship and other problems.

So, here’s your food for thought this weekend: Does your need for certainty cause you needless worry? Whether this is the case of the need for delivery today, political conviction, or sheer reliance on an tech company's promise—are you getting into the certainty trap?

It's time to remind yourself as Wallace puts it:

It is about the real value of a real education, which has almost nothing to do with knowledge, and everything to do with simple awareness; awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over: “This is water.” “This is water.”

Roundups

How Businesses Profit by Wasting Your Time

Greg Rosalsky explains in NPR that the Biden-Harris administration is cracking down on time-wasting corporate practices through its "Time Is Money" initiative. Companies often design frustrating processes—like making it difficult to cancel subscriptions—to increase profits. This initiative aims to prevent such tactics, with the Federal Trade Commission introducing rules to simplify consumer experiences. These actions reflect broader efforts to curb corporate "sludge," where complicated procedures impede consumers from making informed decisions. With parallels in India’s digital reforms, the question remains: can government regulation improve customer experience where the free market falls short? Read it here: Link

Still Fighting the Tobacco Industry

Health communications expert Lucy Popova explains in Knowable Magazine that as vaping rises, so do concerns about its health impacts—especially on young people. While tobacco warnings, like graphic images on cigarette packs, have helped reduce smoking rates globally, similar strategies for e-cigarettes face legal hurdles and evolving science. India banned e-cigarettes in 2019, the US still debates whether pictorial warnings will work for vaping. Graphic warnings can deter smoking, yet their impact fades over time. Much like food labels make us reconsider our choices, these images force smokers and vapers to confront the risks—though they may not be enough alone. In Canada, even individual cigarettes now carry warnings.

“If countries have to keep revising their warning labels so they remain effective, will this continue until warning labels cover practically the whole pack and every cigarette?”, she asks.

With vaping becoming popular among youth, researchers continue to grapple if messages like “nicotine is an addictive chemical” really compete with fruity flavours? Just warning labels aim to prevent risky behaviours—but will they work this time? Read it here: Link

How Urban Design Impacts Air, Heat, and Health

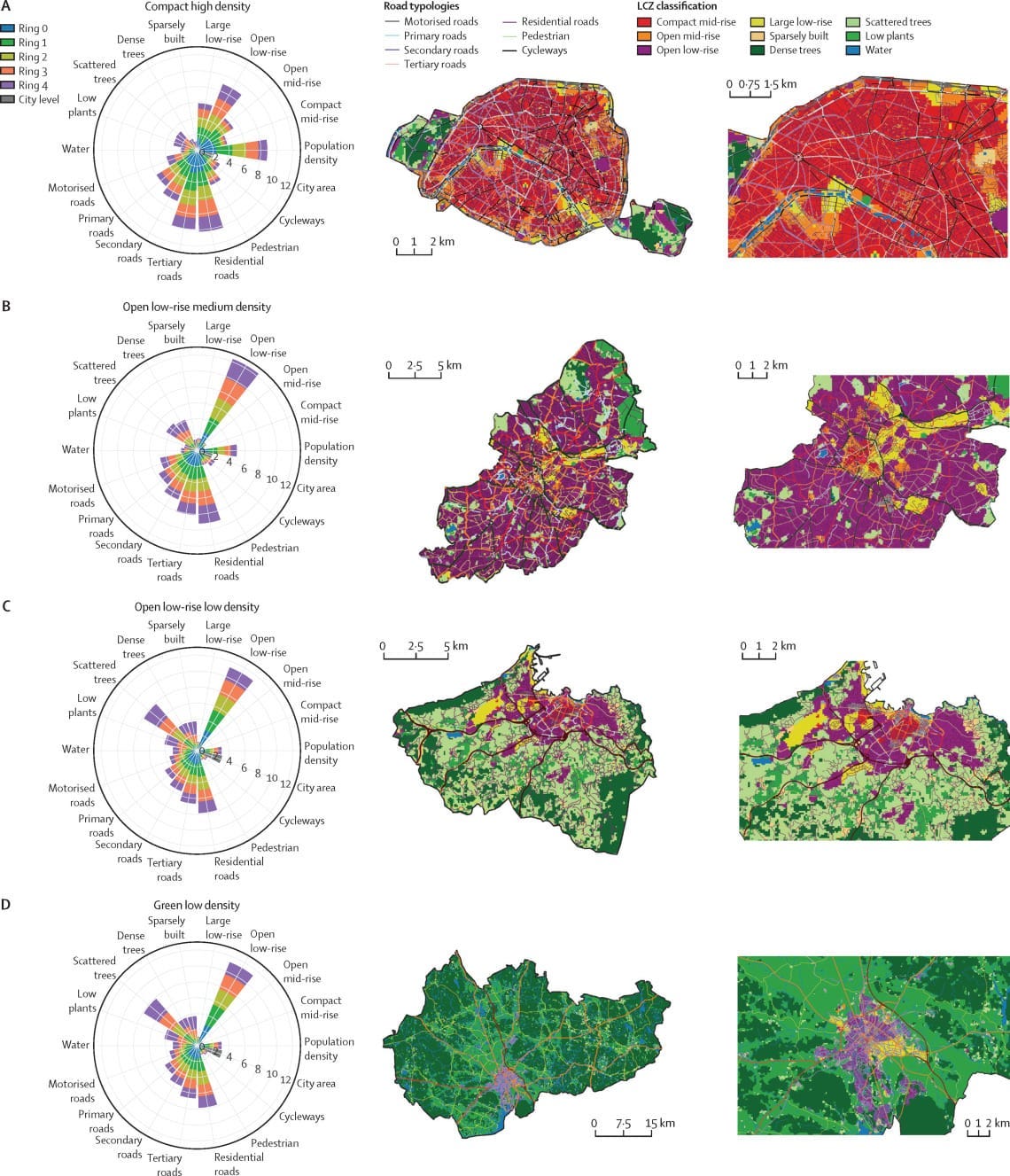

A Lancet study of 919 European cities found that densely packed cities (with more buildings and people) tend to have worse air quality, hotter temperatures, and higher mortality rates, despite producing less CO2 per person. On the other hand, cities with more green spaces (fewer buildings and people) offer cleaner air, lower temperatures, and lower mortality, but emit more CO2 per resident. This reveals a crucial trade-off between environmental sustainability and public health, emphasising the need for smarter urban planning that balances both. Read the study here: Link

Behavioural Guide for 2024 is here

The 2024 Behavioural Economics Guide reveals how behavioural insights are reshaping decision-making across various sectors, from policy to business. Notably, it highlights the growing acceptance of behavioural economics as a key tool for improving organisational performance, influencing democracy, and enhancing sustainability. A significant theme is the use of personalised nudges and AI to optimise outcomes. With growing acceptance in policy and business, behavioural economics is shifting from theory to actionable strategies. Challenges such as replication issues and ethical concerns over AI remain, but the guide emphasises the role behavioural science cam play in creating positive impacts. Read the 2024 report here: Link

💡 Written by Farheen