When Media Becomes the Copyright Police: Legal Right or Strategic Tool?

In a country where mainstream media outlets claimed to be the fourth pillar of democracy, their new role as copyright police is something to worry about. A recent report of the Reporters Collective surrounding Asian News International (ANI) and its use of the copyright enforcement mechanism on YouTube to silence political bloggers is a story of a crisis deeper than a technicalities of law. It is about power, hypocrisy, and of the erosion of accountability in Indian media.

At the centre of the story is ANI’s strategic use of copyright claims against independent YouTubers accused of using short clips from ANI’s coverage to demand exorbitant sums reportedly between ₹15 to ₹40 lakh from them. Many of these YouTubers are political commentators, journalists, and critics of the government who use news footage under the principle of fair use to critique, parody, or analyse current affairs and not for mere entertainment.

Legally, copyright protects original expression. Ethically, it should protect the creative spirit and should not be used as a tool to intimidate. This becomes more problematic when the same media platforms accusing others of infringement have often themselves walked the grey line of content appropriation, when they themselves use viral social media videos without consent, lifting visual content from smaller creators or public events, and amplifying unverifiable or misleading footage during high-tension moments.

Take, for instance, the numerous instances during recent India-Pakistan cross border tension when prime-time channels have run unverified footage as "exclusive breaking news." The ethical and legal boundaries of attribution, verification, and consent are conveniently ignored in the rush for ratings and narrative control. So when the same institutions literally turn overnight into copyright enforcers to safeguard their commercial and political agenda, the hypocrisy becomes hard to ignore.

The real issue here is not whether ANI can sue copyright infringement. It is whether or not someone can decide what is fair, and who can afford to challenge it. Section 52 of the Copyright Act does allow for "fair dealing" in the case of criticism, review, and reporting. But the law is ambiguous, and judicial interpretations are inconsistent. In practice, creators need to prove “fairness” in court, against powerful, litigious media giants, all while their content is already taken down and their revenue hit.

Platforms like YouTube worsen this disparity. Its three claim strike system, can result in permanent channel deletion acts as a coercive pressure point. Creators are given seven days to respond, but not enough time or tools to fight back. As result the creators face financial ruin and with years of work at stake, are left with no other option but to simply pay up, regardless of whether they actually infringed.

If not controlled, copyright enforcement has the potential to become a vehicle for censorship not just of speech, but of political opposition and alternative narratives. It enables dominant media conglomerates to prioritize their information monopoly at the expense of independent commentators.

And the implications do not stop with YouTube. What happens if ANI’s model is replicated across platforms? If old media companies start charging copyright royalties to independent creators who incorporate news footage for commentary or news of public interest, it could turn news footage, something that should be a public good, into a tool available only to massive corporations. In a democracy, this paves the way for further entrenching information inequality.

Even more troubling is that this practice emerges at a time when the credibility of mainstream media is at its lowest. The press, which should serve as check on power, is often seen parroting official lines or serving corporate-political agendas. YouTube, with its relatively open architecture, has become a refuge for alternate voices and narratives. Many of them are independent journalists, satirists, citizen reporters and ex journalists ignored by hierarchy of media houses.

There is no denying that intellectual property deserves protection. But copyright was never meant to be a sword against speech, especially not in journalism, a field that thrives on the free flow of information. But if the press is so fragile that it must resort to copyright threats to defend itself from satire or scrutiny, it has already lost the trust it claims to uphold.

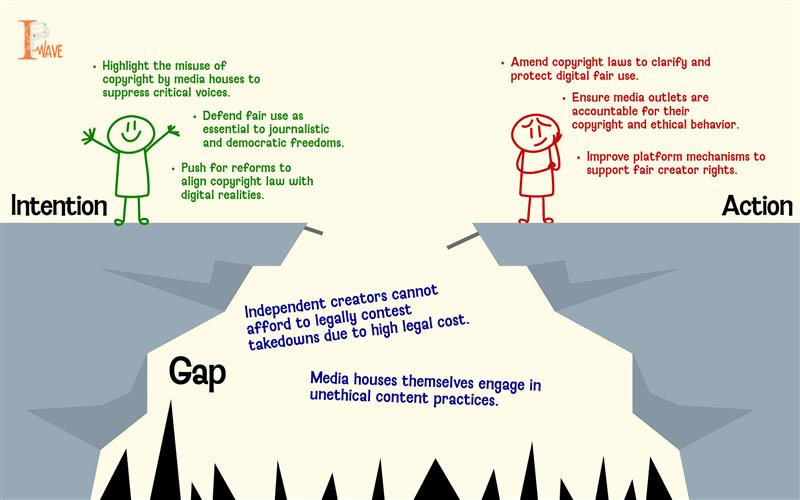

This demands immediate reform, the copyright law was intended for print media and not suited for digital times. The Indian government needs to provide transparency to fair dealing provisions, particularly to political and digital content. And media establishments need to be held accountable both for their handling of copyright and for their own copyrights and practices of use of content and misinformation.

We are witnessing a shift from journalism as public service to media as private enforcer. The fight over copyright is not just about intellectual property. It is about who gets to speak, who gets heard, who gets silenced and who gets to decides “fair use” in digital era.