What India Can Learn from Game Theory on IP Enforcement

Imagine you’re a firm in India tinkering with a new diagnostic algorithm or a textile pattern embedded with sensors. You’ve sunk money into R&D, filed the necessary forms, and are awaiting recognition or maybe just hoping not to be copied before the ink dries. Now imagine your competitor, armed with no such paperwork, beats you to market with a near-identical product. Your options? Sue, a costly, slow process. Or move on. Many firms, as it turns out, quietly choose the latter.

But here’s where it gets interesting.

A 2022 study by Prof. Qianqian Gu and Prof. Lei Hang from Shanghai Normal University, published in Sustainability, uses evolutionary game theory to simulate this dynamic. Their central premise is deceptively simple: firms and regulators do not act like textbook rational actors. They adapt, imitate, retreat, and evolve often in response to one another’s past moves, institutional cues, and the perceived balance between risk and reward.

The model pits local governments and innovative enterprises against each other in a long-term game. Each player has two options: firms can choose to infringe or not; governments can choose to supervise or look away. The results, like any good game, hinge on payoff structures.

In high-enforcement regimes (where regulators punish frequently and harshly), firms initially comply but only so long as the regulatory pressure persists. Once it eases, infringement rebounds. This creates what Professors Gu and Hang call a “fragile compliance equilibrium,” expensive to maintain and inherently unstable. But things get interesting when incentives enter the equation.

Caption: (Gu, Q., & Hang, L. (2022) Each line shows that, regardless of starting point, firms converge to non-infringement but only with costly government oversight.

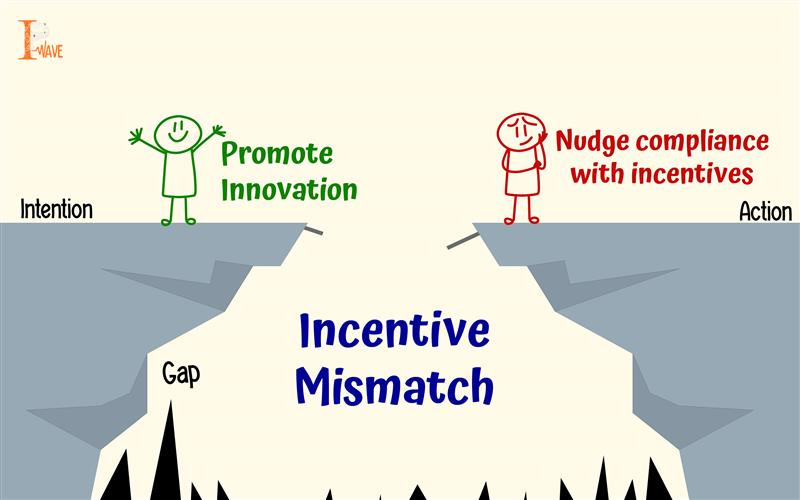

Offer tax subsidies, grants, or reputational rewards to firms for genuine innovation, and they begin to internalise compliance, even when regulators stop watching. The game stabilises not through fear, but through aligned interest. (Refer to Figure 11 - a simulation where high innovation rewards nudge firms to evolve towards non-infringement without supervision.) The model’s implications for India are hard to ignore.

Caption: Gu, Q., & Hang, L. (2022) , When firms receive strong innovation incentives, they shift toward legal behaviour even without government supervision.

While enforcement remains the headline act, with IP raids, court filings, and references in the USTR’s Special 301 Watch List, the underlying actors in the system lack incentives. Enforcement here is adversarial, centralised, and often reactive. Meanwhile, few credible, sustained incentives exist for firms that play by the rules. What Gu and Hang’s work gently nudges us to consider is that perhaps India doesn’t just need more enforcement. It needs better strategic interaction.

This means viewing IP regulation not as a one-shot punishment game, but as an evolving relationship between enterprise and state. Offer firms a reason to believe that playing fair is more profitable than infringing, and they just might play along, for good.

Not because someone’s watching, but because the game itself has changed. And perhaps that’s the point: better rules don’t just punish bad moves; they rewire the incentives that shape the play.