What Cultural Economists Know That Patent Lawyers Don’t

India is trying to do something quite ambitious: turn its culture into economic value.

Across the country, creativity is alive and thriving, animation studios in Hyderabad, indie game developers in Bengaluru, revived Lambadi embroidery in Telangana, and short-video creators who found their voice after TikTok’s exit. But the laws meant to protect creative work, our IP system, still ask the wrong questions.

Did you invent something completely new?

Can you show clear, individual authorship?

Do you have the paperwork to prove it?

In today’s world, where value is often cultural and collective, these questions aren’t just outdated, they leave entire sectors behind.

That’s the concern economist Nicola Searle raises in her work on creative industries. In her essay Cultural Economics, Innovation and Intellectual Property, she challenges the usual thinking: that IP is all about protecting private, patentable inventions. What if we looked at IP from the ground up through the lens of creators, not just companies or codified systems?

Australian scholar Miranda Forsyth, writing about the Pacific Islands, goes one step further: trying to impose individualistic, Western IP norms on collective and customary creative systems, she argues, creates “tensions between individual autonomy and family and community obligations.”Let’s try applying that lens to India.

The Real Size of India’s Creative Economy

Our cultural industries, music, crafts, film, fashion, design, folklore, storytelling, employ millions, often in informal ways. Yet when IP policy is discussed, it's rarely about them. The focus remains on biotech patents, pharma disputes, and trade agreements. GI tags like Mysore silk get an occasional mention, but how often does the actual weaver benefit?

The answer, sadly, is: not very often.

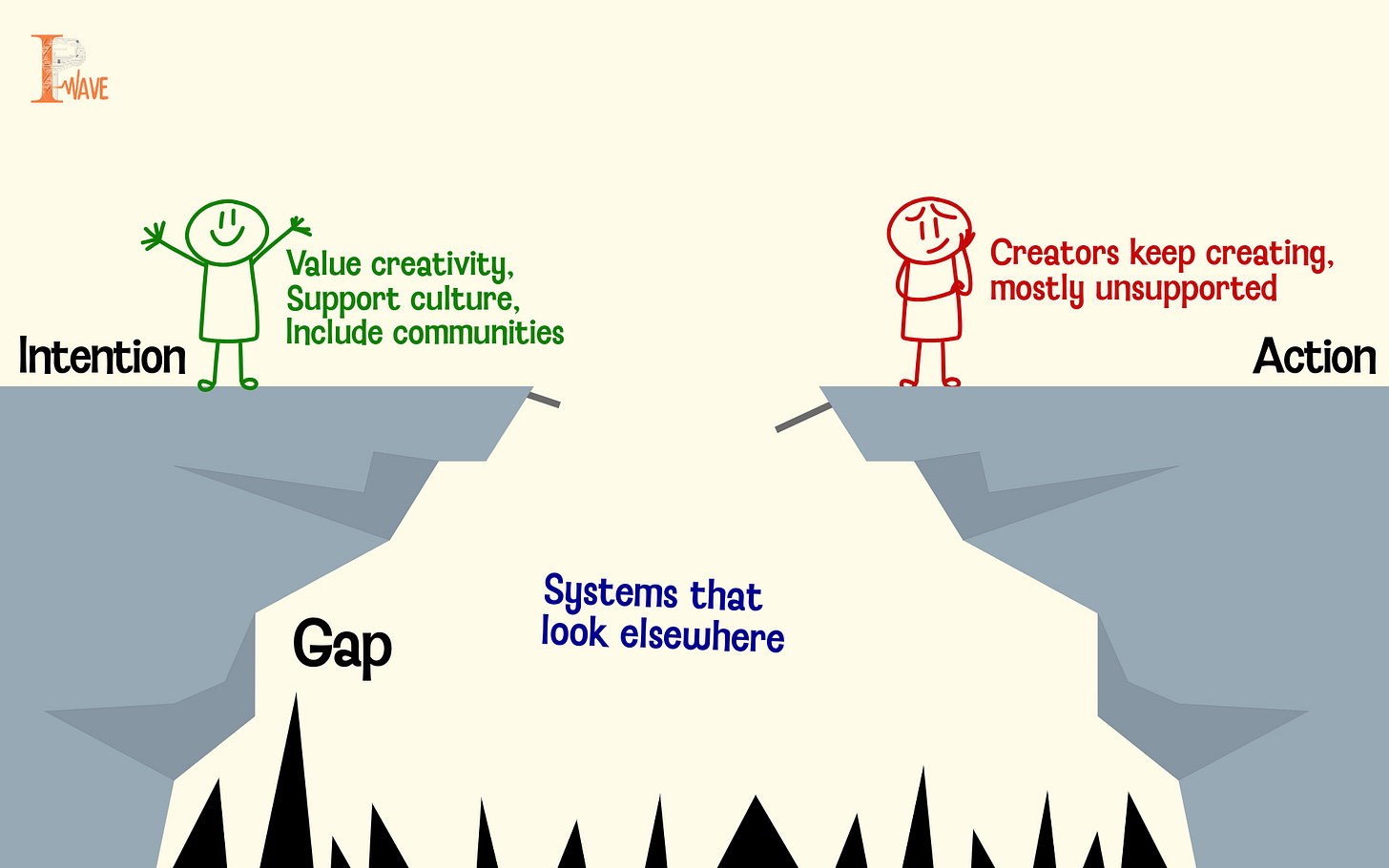

According to Searle, this isn’t a mistake, it’s a design flaw. Most global IP systems were built for economies where innovation is individual, commercialised, and proprietary. But in India, creativity is often shared, built over time, and rooted in community. It doesn’t always look like “invention,” and that’s where it slips through the cracks.

So much of what we call innovation in India isn’t about a single “eureka” moment. It’s slow, adaptive, iterative.

Searle calls this " soft innovation"; its a remix, a reinterpretation, or an update.

Caption: Chenda player from Kerala @mr_chendakkaran

A Phulkari pattern adapted digitally for export? That’s innovation.

A folk musician updating rhythms to go viral on Instagram? Also innovation.

A gaming studio reimagining Indian mythology for a global audience? Without question.

But the law doesn’t always see it that way. Copyrights don’t handle group authorship well. GI protections are patchy and poorly enforced. Traditional knowledge laws still sit in isolated government files.

The Problem Isn’t Just the Law - It’s the Incentives

Searle makes another key point: IP isn’t just about protecting ownership, it’s about shaping behaviour. Right now, our system mostly rewards those who understand how to navigate it, those with legal access, paperwork, and patience.

But what about the Ahmedabad designer who sees her print show up in a Delhi boutique with no credit? Or the tribal artist whose motifs are copied by a luxury brand for the global runway? They don’t sue. They don’t have time. And they’re not even sure the system would help if they tried.

India’s creative economy isn’t short on talent. It’s short on systems that understand how that talent actually works.

Three things can help change this.

1. Support Community Ownership

Let’s stop treating creativity like it always comes from individuals. Many forms of art and knowledge in India come from communities, village weavers, tribal groups, cooperatives. IP policy should give them ways to protect and benefit from their work together.

2. Recognise Everyday Innovation

Not all innovation is high-tech. A lot of it is local, practical, and deeply rooted in culture, jugaad, traditional knowledge, clever reuse. The law should treat that as valuable, too.

3. Give Creators a Real Toolkit

Legal help shouldn’t come only after there’s a dispute. There could be a basic IP toolkit: easy-to-use templates, simple group registration processes, fast-track support for GIs, and community-level dispute help. Turn IP from a maze into something usable from day one.

India’s next big leap might not come from code or clean tech. It could come from how we support and scale our cultural strengths. But to unlock that, we need to stop thinking of IP as just a legal shield and start seeing it as part of our development strategy.

Not just more enforcement.

Not just more forms.

But a fresh way of thinking about creativity itself.

That’s what cultural economists like Nicola Searle understand.

And it’s what many patent lawyers and even our policymakers still don’t.