Touchscreens on Wheels: How Indian Roads Are Being Put at Risk by In-Car Entertainment

Every day, my colleagues and I take a cab from our office in Vasant Kunj to Kalkaji Mandir. During these rides, I’ve noticed something concerning drivers often watch movies or music videos on screens while navigating through evening traffic. They seem to assume their familiarity with these routes—honed over years of driving—makes this behavior safe. This reflects a troubling reality in India: overconfidence often trumps caution.

Government enforces strict rules on seatbelts and phone use, yet traffic police turn an impartial eye to screens playing in cars. I assumed built-in car systems would halt video playback once the vehicle starts moving, but they don’t. Why? Many cabs—and I suspect countless private cars—sport aftermarket touchscreens, installed under the guise of “modifying” the vehicle. These cheap/or luxurious displays, unlike factory-installed systems, lack safety features to disable videos while driving.

India’s roads are deadly. The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH) reported 461,312 accidents in 2022, with 422 deaths and 1,130 crashes daily. Over 3,000 fatalities that year were linked to mobile phone use. Traffic accidents don’t just claim lives—they inflict profound social and economic losses. While we lack specific data on touchscreen-related crashes, the behavior I’ve witnessed—drivers engrossed in Bollywood films despite traffic rules and passenger safety—suggests a reckless disregard for consequences. They do not put their life but their co passengers' lives on stake. Globally, the burden of disease estimates a death rate of 17.11 per 100,000 people due to traffic injuries in 2021. In India, where the driving age starts at 18, MoRTH data shows 66% of 2022 road accidents involved people aged 18-45—a demographic central to our workforce.

Aftermarket screens, costing between ₹15,000 and ₹20,000, play videos nonstop, turning cabs into rolling theaters. Even factory-installed systems—for radio, AC, or navigation—demand too much attention. Where on one hand, use of touchscreen devices in cars is a convenient human – technology interaction, leveling up the interior aesthetics, it's also causing visual manual distraction. In a research experiment for a study shows performance of drivers was significantly impaired in using touchscreen in cars. Research by David Strayer at the University of Utah shows touchscreen tasks take twice as long as physical buttons. In India’s chaotic traffic, where potholes and rickshaws demand split-second reactions, those extra seconds can be fatal. A 2020 UK Transport Research Lab study found touchscreen use slows reaction times by up to 57%—worse than alcohol’s 12% impairment. The University of Utah and UK studies also linked touchscreens to delayed reactions, lane departures, and a higher crash risk, with 1,000 fatal U.S. crashes in 2017 tied to in-vehicle distractions.

Music, too, plays a dual role. Systematic reviews suggest 70-100% of drivers consider it essential, with 75% listening while driving. For many, it’s a stress reliever or mood booster. Research indicates driving quality hinges on attention, response time, and mood—factors music can influence. Yet its impact is debated: it may calm anger or stress, but it can also increase mental workload. One study claims 25% of accidents stem from listening to music, though the effect depends on the type and volume—details too subjective to generalize.

In India, strict seatbelt laws and fines have saved lives, but touchscreens threaten to undo that progress. Fancy In-Vehicle Information Systems (IVIS)—internet-linked screens for navigation and multimedia—are gaining traction in cars like the Tata Nexon and Hyundai Creta, sparking safety debates. Euro NCAP’s 2026 rules will favor physical buttons to curb distraction, labeling touchscreens an “industry-wide problem.” In India, the stakes are higher: drivers play movies mid-journey, treating roads like entertainment zones.

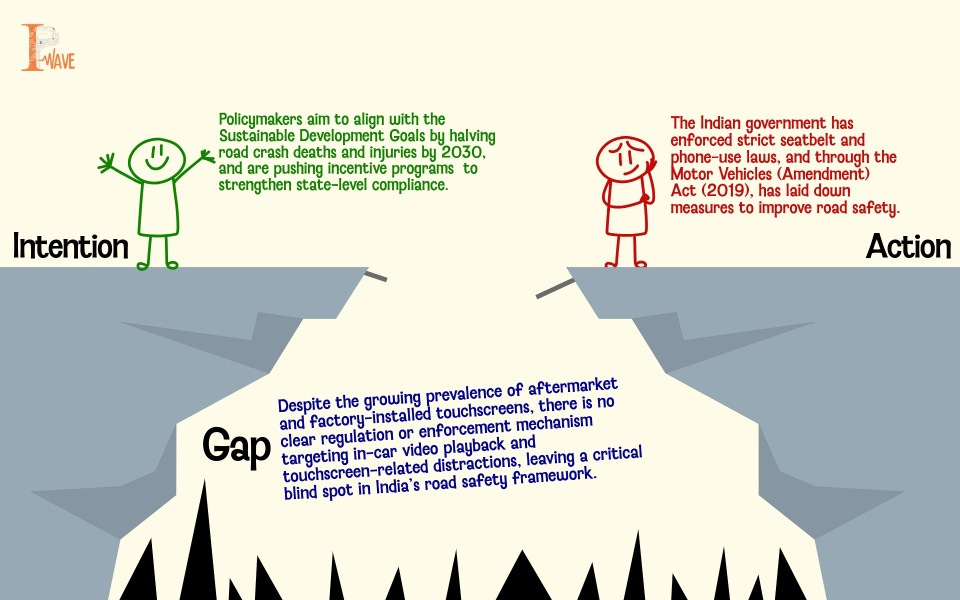

Policymakers must act. We need studies to quantify touchscreen-related crashes, stricter police reporting, and clear regulations—ban video playback while driving, mandate intuitive controls, and penalize reckless use. The World Bank notes South Asia’s rapid vehicle growth drives crashes and fatalities, exacerbated by a heterogeneous mix of transport. India, with the world’s highest reported road crash deaths (1.19 million global deaths annually as per WHO (2019)), faces a unique challenge. The government, a signatory to the Sustainable Development Goals, aims to halve road injuries and deaths by 2030—reducing accidents to around 200,000. Yet, the World Bank & Bloomberg Philanthrophy estimates India needs $109 billion more to meet this target. A 50% fatality reduction could boost GDP by 14% over 24 years, a compelling economic case.

From a policy perspective, regulating touchscreen sales and use is low-hanging fruit. The government should enforce strict checks on aftermarket systems, ensuring they meet safety standards. India’s National Road Safety Strategy (2018-2030) and the Motor Vehicles (Amendment) Act of 2019 aim to reduce fatalities, but implementation lags. The Indian government is also working on a US$2 billion State Road Safety Incentives Program to help the MVAA pass by giving states financial grants to pursue ongoing road safety improvements.