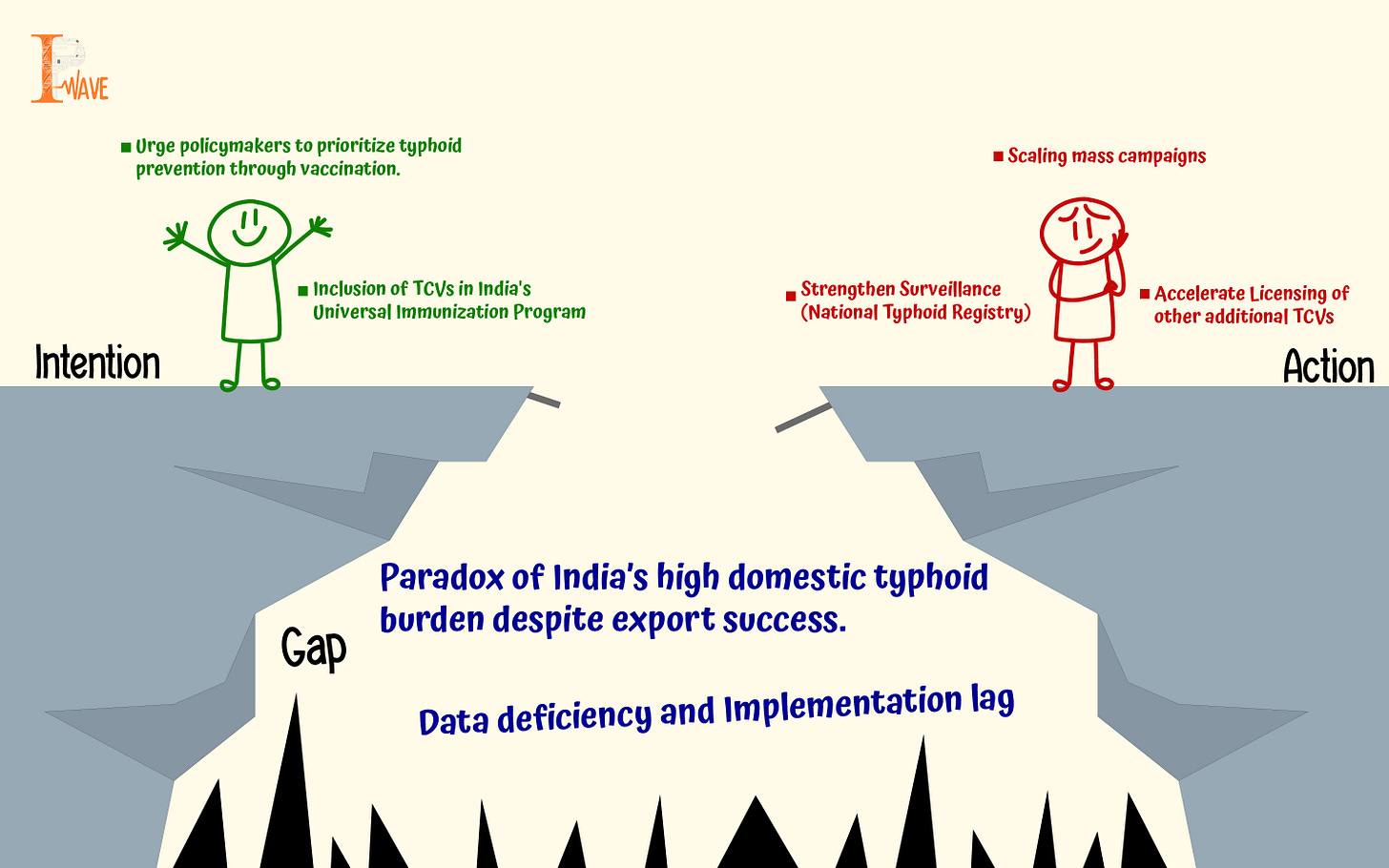

The Typhoid Paradox: The Case of including TCVs in India’s Universal Immunization Program

By Neeti Goutam

India is considered a giant in producing some of the world's best typhoid vaccines, like Bharat Biotech's Typbar TVC and Biological E's TYPHIBEV. Both these vaccines are WHO-prequalified, i.e., eligible for purchase by United Nations agencies. India leads the world in typhoid vaccine exports. According to the Volza estimates, for the year 2023-2024, there were 45 Indian exporters and 89 buyers of the typhoid vaccine. However, in India, half of the global burden is faced with this disease yearly. This raises a critical question: why does a country that excels in manufacturing these vaccines not shield its own people from the preventable disease?

Typhoid is a public health issue globally, going critical in low- and middle-income countries. Every year, globally 11-20 million people suffer from the infection, and 0.128- 0.161 million die from this enteric disease/fever. According to the Global Burden of Disease, South Asia has the highest burden of typhoid cases (70% of the cases and mortality globally), and India alone accounts for 82% of incidence and 75% of mortality in South Asia. India, which has half of the global typhoid disease burden, has a very high incidence rate. WHO estimates the rate of incidence in India from 282.4 per 1,000,000 population in 2022 to 399.2 per 1,000,000 population. In 2023, the reported cases were around 5,74,129. Surveillance of Enteric Fever in India (SEFI) estimated 576-1173 cases per 100,000 person years (person-years means a unit of measurement that quantifies the total time a group of individuals are at risk of developing a disease or event over a specified period) between the years 2017-2020, particularly in children living in urban areas. SEFI surveillance data shows the highest incidence of 770 per 100,000 person- years among the age group 5-9 years, followed by 566 (per 100,000 person- years) among 10-14 years. The disease also places the burden on the country’s economic and social wealth in terms of high hospitalisation rates (mean direct cost ranges between 8 thousand and 29 thousand INR). Also, on average, each case of typhoid fever resulted in 16.4 days of leave from school and 4.5 days of absence from work.

What causes typhoid fever?

Typhoid fever is caused by the gram-negative bacterium Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhi (S. Typhi). The main sources of infection are the urine and stool of the infected person, infected water, and food. It can spread to any part of the body (mostly gastrointestinal) and can cause organ damage. The disease is common in places with a lack of sanitation and hygiene practices. If not treated timely and early, the disease can be fatal. The most vulnerable age group that the bacteria targets is children (mainly under the age of 15). The cases are rampant in India and South Asia where extreme weather events impact water and food quality.

Globally, the successful treatment of typhoid is using antibiotics. However, the use of antibiotics has also become challenging due to the growing incidence of antibiotic resistance. Infection caused by drug-resistant S. typhi leads to increased mortality and morbidities. Despite being the leading country in typhoid vaccine exports, India may not be prioritizing widespread access to these vaccines for the country.

Due to these conditions, WHO has included typhoid vaccines as a priority disease in their essential medicine list. WHO has continuously recommended including newer licensed vaccines in the nation’s immunization program. However, there is a time lag between the recommendation and implementation. One such example is the non-inclusion of typhoid vaccines in India’s Universal Immunization Programme.

Availability and Effectiveness of Typhoid vaccines in India

There are four licensed typhoid conjugate vaccines (intramuscular) available in India. TCV vaccines are recommended by WHO and by India’s Technical Advisory Group on Immunization (NTAGI) for introduction in the Universal Immunization Program (UIP) in 2022; they are suitable for younger children and all ages and provide long-term protection. Two of them are WHO-prequalified vaccines. India was the first country to develop the licensed TCV vaccine (Typbar – TCV by Bharat Biotech).

The safety and efficacy of TCV were evaluated in India through the mass campaign in Navi Mumbai, covering more than 159,831 children (below 15 years); populations showed vaccine effectiveness of about 82% among children 9 months and older, mostly in Pakistan, Zimbabwe, and Malawi (ranging from 71%-98%). However, the onset of COVID -19 pandemic prevented the second stage of trials in Mumbai. The Cost of TCV vaccine delivery using Typbar - TCV in urban health centers of Navi Mumbai during the campaign ranged from 1.37 dollars to 3.98 dollars per dose. This shows that similar campaigns can prove positive results, and India’s vaccine giants can solve this problem. Large clinical trials in Malawi, Nepal, and Bangladesh showed a 78%-85% efficacy rate (efficacy at least for 3 years). Research suggests five countries, namely Pakistan, Liberia, Nepal, Zimbabwe, and Samoa (two of our neighbouring countries), have introduced TCV into their national immunization programs (costing just about 1.5 dollars to 2.00 dollars per dose), yet a number of typhoid-endemic countries have not made the decision yet, with India being one of them. Organisations like WHO and GAVI have accepted TCV, leading to discussions for change in global typhoid policy that started in 2017. GAVI is committed to funding 85 million dollars for TCV introduction in countries, mostly from low- and middle-income countries. Till 2020, 57 countries were eligible, including India for new vaccine support from GAVI. Another vaccine, named TYPIBEV by Biological E India, received WHO prequalification in 2020. In India, the TCV vaccine was first recommended in 2013 by the Indian Academy of Paediatrics, which led to an increase in the sale of TCV in the private market (3.3% of the birth cohort in 2012-2015), suggesting acceptance in the private market. Decision makers should prioritise and consider the success of these programs with other health priorities.

India has sparse data and limited population-level data, hospital data, and community data to measure the extent of variation of typhoid cases in India, which is a bane when it comes to controlling the cases that rise with respect to conditions like climate change, water scarcity, and challenges of antimicrobial resistance. There is a need to estimate the impact of TCV (in terms of cost of implementation) on the national immunization program with support from GAVI and, more importantly, whether India’s health system can accommodate that budget or not. Research strongly suggests that in India TCV introduction is cost-saving in urban settings. Additionally, when compared with the indirect cost of the fever, which includes productivity loss. There are more TCVs in various stages of development and licensing, which is important to meet our country's and the global demand. Vaccines like pedaTyph by Biomed India are licensed to use in India but lack WHO prequalification due to insufficient data. ZyVAC TCV from Zydus Lifesciences Ltd., India, got WHO’s nod in October 2024 and is effective in age groups 6 months to 65 years of age. To conclude, with proven TCV vaccine efficacy on one hand and growing antimicrobial resistance on the other, the integration of typhoid conjugate vaccines into India’s Universal Immunization Program has never been stronger.

The Intellectual Property and Innovation Role

India's typhoid vaccine innovation is backed by high R&D investments and intellectual property protection. The innovation of Typbar-TCV by Bharat Biotech's was a world's first in typhoid conjugate vaccine innovation, and the firm was awarded several patents in India and globally for new compositions, conjugation technology, and vaccine stabilization. Similarly, Bip TYPHIBEV reflects domestically driven biotechnological innovation supported by robust IP regimes. Both vaccines' WHO prequalification not only establishes their quality and efficacy but also increases global marketability with IP-backed licencing agreements. While patent protection has allowed Indian companies to fund R&D fees and increase global exports, it also poses concerns of crucial policies towards access and affordability in the domestic market. The challenge of the future is balancing incentives for innovation with public health priorities by leveraging IP with public procuring, invoking compulsory licensing terms when required, and incorporating the patented vaccines into universal healthcare packages.