The Rise and Risk of India’s Prediction Platforms

The idea of betting on the future is hardly new. From the satta bazaars of pre-independence India to online fantasy leagues today, the line between speculation and skill has always been blurry. But in recent years, a new breed of digital platforms, styled as “opinion trading” markets, has complicated that boundary even further. Apps like Probo and Better Opinions allow users to trade positions on real-world events: whether a cricketer will score a half-century, whether gold prices will rise by Friday, or if a YouTube video will cross 10 million views.

The format feels familiar. A “yes” and a “no,” a price assigned to each side, and a payout if you’re right. To the casual user, it resembles stock trading. To the cautious observer, it mimics gambling. And to India’s regulators? It sits squarely in a legal and conceptual no man’s land.

Not Quite Securities, Not Quite Games

At the heart of this regulatory ambiguity is a deceptively simple question: are prediction markets financial instruments or games of skill?

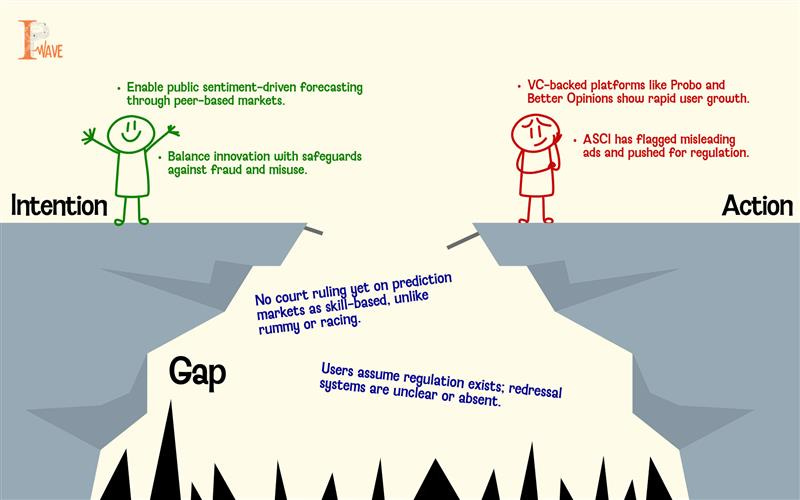

SEBI, India’s securities regulator, has opted to stay away. Since these products do not involve traditional securities, SEBI has declared them out of its jurisdiction. The Ministry of Electronics and IT (MeitY), which now oversees online gaming, has not stepped in either. That leaves platforms to self-classify, most declaring themselves as skill-based games.

This isn’t without precedent. Indian courts have historically protected games like rummy and horse racing under the “skill” exception, arguing that outcomes can be reasonably predicted by informed players. However, the same courts have also flagged the dangers of indiscriminate bans, striking down blanket prohibitions in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka for not distinguishing between skill and chance.

Prediction markets complicate this divide. As the Esya Centre points out, these platforms reward users who apply data, domain knowledge and analytical tools, but outcomes are still swayed by luck, sentiment, or sheer randomness. This makes it difficult to classify them neatly. As with futures trading, a trader’s success may owe more to fortune than foresight.

What the World Is Doing

Globally, regulatory responses vary. The UK treats prediction markets as a subset of gambling. The US CFTC, in a high-profile legal battle, tried to block Kalshi from offering contracts on political outcomes, arguing they constituted illegal gaming. But a federal court pushed back, limiting the CFTC’s definition of “gaming” and allowing Kalshi to operate. In Europe, the ESMA has taken a hard stance, banning binary options for retail investors.

Closer home, India’s Advertising Standards Council (ASCI) has expressed concern about how these platforms market themselves. With over 5 crore Indian users, many of whom assume these are regulated financial products, the potential for misleading advertising is real. Phrases like “profits,” “stop-loss,” and “trading” evoke the stock market, but these apps lack any formal oversight. There is no investor protection, no grievance redressal, and no regulatory body monitoring outcomes or disputes.

The Platforms’ Defence

Platforms like Probo and Better Opinions defend their model as participatory, transparent, and educational. They argue that trading on cricket, elections, or entertainment brings finance closer to everyday life. In their view, prediction markets promote financial literacy, democratise decision-making, and reflect collective intelligence.

There is some merit to this. Academic studies, from the Iowa Electronic Markets to recent US elections, show that prediction markets can outperform polls in forecasting accuracy. Users who rely on data and real-world events often beat the averages. But does this make it a financial tool or an intelligent bet?

The Skewed Bet: A Cautionary Tale

What remains deeply underexplored is the skewed reward-to-risk ratio that many users face. For instance, a user betting ₹90 on an event priced at ₹0.90 per share might expect a ₹100 payout if correct, earning ₹10. But if wrong, they lose the entire ₹90. In theory, high-frequency success could offset such losses, but in practice, these trades often rely on volatile or sentiment-driven outcomes. The asymmetry—risking large sums for modest gains—can erode user capital quickly, especially for young or financially untrained users drawn in by gamified interfaces. In the absence of regulation, the burden of risk falls squarely on the consumer.

Sovereignty, Scale, and the Way Forward

As the US tribal gaming debate reveals, this isn’t just about consumer risk. It is also about jurisdiction. In the US, tribal leaders worry that unregulated prediction markets undermine long-standing compacts and centralise control in platforms. In India, where online gaming is increasingly governed by both state and central laws, a similar question looms: who decides?

If these platforms are classified as financial products, SEBI must step in. If they are games of skill, MeitY and state gaming laws may apply. Either way, the current vacuum is untenable. Without regulatory clarity, consumers remain exposed, investor confidence remains conditional, and innovation walks a tightrope.

Perhaps the first step is to stop asking whether prediction markets are “good” or “bad.” The better question is how to design guardrails that preserve innovation while preventing exploitation. Until then, India’s opinion trading boom remains a curious, cautionary tale of finance without regulators, games without rules, and the high stakes of betting on the future.