The Raga, the Rights & the Rahman Row: When Dhrupad Met the High Court

On the occasion of World Intellectual Property Day 2025, with this year’s global theme “IP and Music: Feel the Beat”, the article explore the intersection of ancient musical heritage and modern media.

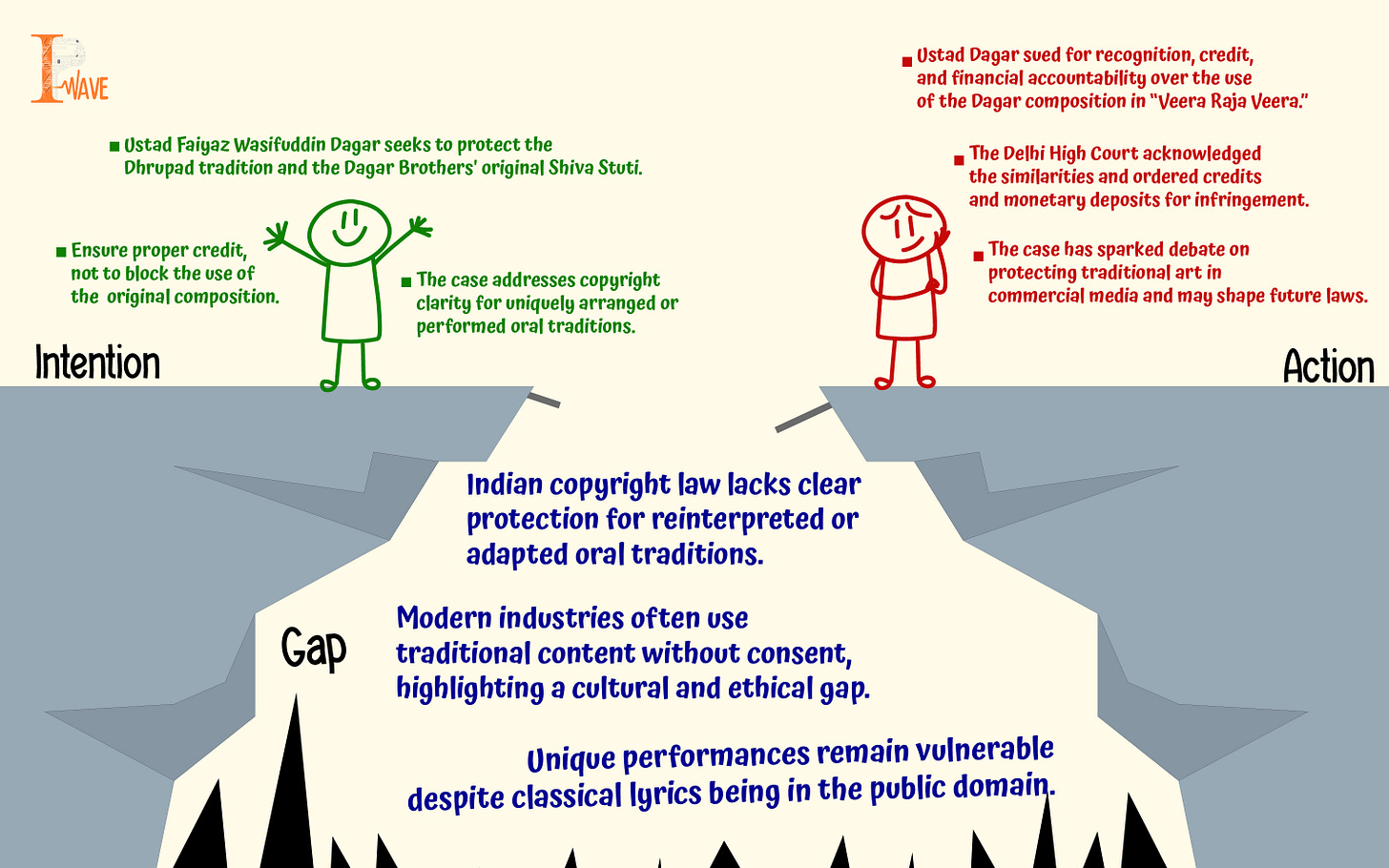

Sometimes, a legal battle is more than just a matter of law—it’s a question of legacy, art, and the invisible lines between reverence and reproduction. That’s exactly what has unfolded in the ongoing copyright dispute between Ustad Faiyaz Wasifuddin Dagar, a venerated voice in Indian classical music, and the globally renowned composer A.R. Rahman. At stake? A centuries-old raga, a chart-topping film track, and the soul of a musical tradition.

It all began when Ponniyin Selvan: Part Two, the sequel to Mani Ratnam’s grand historical epic, hit theatres in 2023. Among its standout elements was the stirring anthem “Veera Raja Veera”, a track that struck a chord with listeners for its deep classical roots and rhythmic intensity. But for those immersed in the ancient art of Dhrupad, the song stirred something else entirely: recognition. Too much recognition.

Ustad Faiyaz Wasifuddin Dagar, the sole surviving performer from the 20-generation-old Dagar lineage, says Dhrupad didn’t just inspire the melody—it was lifted from it. More specifically, he argues it mirrors a rendition of “Shiva Stuti”, originally performed and composed by his father and uncle—the Junior Dagar Brothers—in the 1970s. Their performance, rich in devotional gravitas and musical precision, was recorded live in Amsterdam in 1978. According to Ustad Dagar, what audiences heard in “Veera Raja Veera” wasn’t homage—it was replication.

This case is especially poignant because of the alleged infringement and the emotional and cultural weight it carries. Dhrupad isn’t just music. For the Dagar family, it’s a living, breathing inheritance—sacred, practised, and preserved through generations of oral tradition and spiritual discipline. To see their signature composition transformed into a commercial soundtrack, without consent or credit, felt like more than a breach of copyright—it felt like a breach of trust.

Justice Prathiba M. Singh appeared to recognise the complexity as the matter reached the Delhi High Court. The Court ordered A.R. Rahman to submit the raw, unedited studio song recording for detailed analysis. The petitioner, meanwhile, presented structured musical comparisons—identifying parallels in the beat (chautaal), raga (Adana), tempo, and even stylistic delivery. The similarities, on paper and in sound, were compelling.

The defendants, however, were quick to defend their ground. They argued that the song was based on a traditional Sanskrit composition attributed to the 13th-century scholar Narayana Panditacharya. As such, it lies within the public domain—freely available for interpretation. In their view, while Dhrupad may provide the stylistic flavour, the composition itself wasn’t anyone’s exclusive property. And crucially, they asserted that one cannot copyright a "manner of singing."

But the case goes beyond legal doctrine. It raises questions about how ancient forms are used in modern media, and whether artists from traditional backgrounds are given the recognition—and protection—they deserve.

Legal and Cultural Analysis

Under Indian copyright law, traditional material from the public domain can be freely adapted. However, if someone creates a new and distinct arrangement of that material, especially one fixed in a tangible form like a recording, it can be protected as an original work. That’s the crux of Ustad Dagar’s claim: that the Junior Dagar Brothers’ Shiva Stuti was not merely a performance of an old chant but an artistic reimagining with unique melodic phrasing, rhythmic structure, and vocal nuance.

The defendants, meanwhile, are standing on the other side of the legal line, suggesting that this was not a case of copying but of reinterpretation—an act of creative freedom applied to public property. Their argument leans on the idea that ancient devotional lyrics and ragas are part of India's collective cultural fabric, not private artistic assets.

But what complicates this debate is the Dhrupad tradition itself. It has no single author, and no written copyright claim was lodged decades ago. Its legitimacy is oral, intergenerational, and spiritual. For the Dagar family, this lawsuit is not about money but respect. It’s about asking where the boundaries lie when you take something sacred and use it for commercial storytelling.

The implications, whichever way the verdict swings, are enormous. A ruling in Ustad Dagar’s favour could embolden traditional artists to assert rights over their unique interpretations. It might force Bollywood and big music labels to rethink how they borrow from classical roots. On the other hand, ruling for the defence might reinforce the fluid, shared nature of India’s cultural inheritance—but possibly at the cost of erasing the artists who are still keeping that heritage alive.

The Delhi High Court scheduled the next hearing for November 7, 2023, where both parties were directed to submit further evidence, and the court may consider expert musical testimony to understand the technical depth of the compositions involved.

In the meantime, this case has already succeeded in doing what few lawsuits manage—it’s made people listen. Listen to a song, yes, but also to the story behind it. It’s made people ask where art begins, where tradition ends, and whether we’re giving enough space to the keepers of culture in an industry that thrives on speed, soundbites, and spectacle.

Court Sides with Dagar in Interim Relief

In a significant twist to the case, Justice Prathiba M. Singh of the Delhi High Court delivered a significant interim order on April 25, 2025. Observing that “Veera Raja Veera” was “identical” in structure and expression to the Dagar Brothers’ “Shiva Stuti” with only “certain changes,” the court ruled in favour of Ustad Dagar. The court ordered that the film and music credits be updated to include Ustad Nasir Faiyazuddin Dagar and Ustad Zahiruddin Dagar as the original composers. Additionally, the defendants have been directed to deposit ₹2 crores with the court registry and pay ₹2 lakh in costs to the petitioner. This interim relief marks a powerful acknowledgement of artistic authorship in traditional forms and will likely set a precedent for similar cultural copyright cases as we advance.

References: