The Military-Industrial Spiral: How Innovation Becomes Entrenched Doctrine

The acquisition of new technologies by militaries goes far beyond hardware upgrading; it significantly reshapes the way they think about war. A stealth fighter, a new-generation missile system, or a new aircraft carrier does not merely offer new capabilities; it incorporates new doctrines, biases force structure, and hardens strategic presumptions. Over time, this evolves into what can be labeled a military-industrial spiral, in which procurement choices and perceived threats reciprocally support one another in a continuous feedback loop. The result? Forces often train for the last war, not the next one.

At its core are two well-documented forces: the revolving door and path dependence. The first describes the well-trodden path that directs generals, procurement officials, and military commanders into defense contractor careers after retirement. These men and women carry with them a reservoir of institutional knowledge and biases often in favor of the very systems their future employers have developed. The second is a form of strategic inertia: when a military commits to a particular approach; say, manned fighter aircraft or large aircraft carriers, it then constructs multiple layers of training, doctrine, logistics, and career incentives around that decision. Changing direction is thus made expensive and time-consuming, and institutionally discouraged.

The Revolving Door and Strategic Bias

The Pentagon-private sector defense industry revolving door is documented in the United States, the country with the steep lead in quantitative and qualitative defence. Top officials often move on to lucrative positions with firms like Lockheed Martin or Boeing, where they sell the same systems they previously managed. One watchdog report cautions that the trend "confuses what is in the best financial interest of defense contractors… with what is in the best interest of military effectiveness.".

This confusion comes at a very steep price. Both the Pentagon and Congress have extremely difficult political and institutional challenges in terminating programs once they are invested, regardless of any shift in threat dynamics. For instance, the F-35 fighter program has over $10 billion in annual costs. More than 1,000 aircraft are already under contract. Critics caution that this commitment commits the United States Air Force to a manned future until at least the 2050s, even though the demonstrated capabilities of drones and autonomous systems in asymmetric and urban warfare environments are well established.

The consequences extend beyond budget. If a general openly questions an expensive platform, his post-retirement career tends to vanish. "A general attacking the F-35," quips one analyst, "won't be having dinner with defence CEOs in retirement."

Path Dependence: How History Locks In Strategy

Laid on top of that is technological path dependence. Once a military branch has committed to a particular path, e.g., the creation of heavy armor or carrier aviation—the path is virtually impossible to change. Training courses, basic infrastructure, maintenance contracts, and military schools of higher education become accustomed to the system in existence. As one Pentagon study put it, path dependence "can lock the military into obsolete ways of thinking" no longer relevant to today's threats.

The outcome? Militaries spend time defending platforms instead of solving problems. A carrier navy will see deterrence in terms of carrier strike groups. A manned-air-force with thousands of human-piloted aircraft will conceptualize enemies as similarly armed powers, even when the next war might be based on drones, swarms, or cyber weapons.

Carriers, Missiles, and the Red Sea

Take the U.S. Navy's $13 billion USS Gerald R. Ford, which entered service in 2022. Despite having state-of-the-art technology, it is also a huge, conspicuous target in a missile-dense world. China, with the most hypersonic missiles in the world, has created capabilities that can sink a carrier in minutes. A 2025 Pentagon briefing put the Ford at risk of sinking because of a single precision strike. But the U.S. and China double down on carriers, not so much because they're future-proof, but because they conform to current doctrine.

Asymmetric warfare linger underfunded. In the Red Sea, Houthi rebels use low-budget drones and missiles to buzz U.S. warships. The U.S. response? Billion-dollar destroyers and manned fighter patrols that sometimes end up in the bottom of the sea— solutions too often too large and ill-fitting. Drones or disposable systems would be better, but institutional momentum favors legacy assets.

Global Echoes: India, Russia, and Beyond

India's Operation Sindoor followed the same patterns. With UAVs, AI mapping, and automated logistics at its disposal, operations still relied on manpower-fueled strategy and costly fighter sorties. The question wasn't whether decision-makers had access to better tools — but whether they would change old habits. To effectively counter cross-border terrorism, India must embrace newer technologies and revive espionage networks, as conventional military wisdom often falters against unconventional foes. Sparking a national conversation on innovation can enable the government to channel greater investment into R&D tailored for emerging asymmetric threats.

Russia's initial setbacks in Ukraine, as well, indicate that doctrine and reality were mismatched on the battlefield. Depending on massed tanks and shock attacks, Moscow's troops were frustrated by Ukraine's mobile, tech-enabled resistance employing commercial drones and portable weapons supplied by the West.

In Pakistan, 2023 counterinsurgency was more akin to 2000s playbooks — massive troop deployments at the cost of precision surveillance. In Gaza, Israel's cutting-edge technology has too often been substituted by raw air campaigns, even though it has access to more accurate, AI-powered ISR capacities.

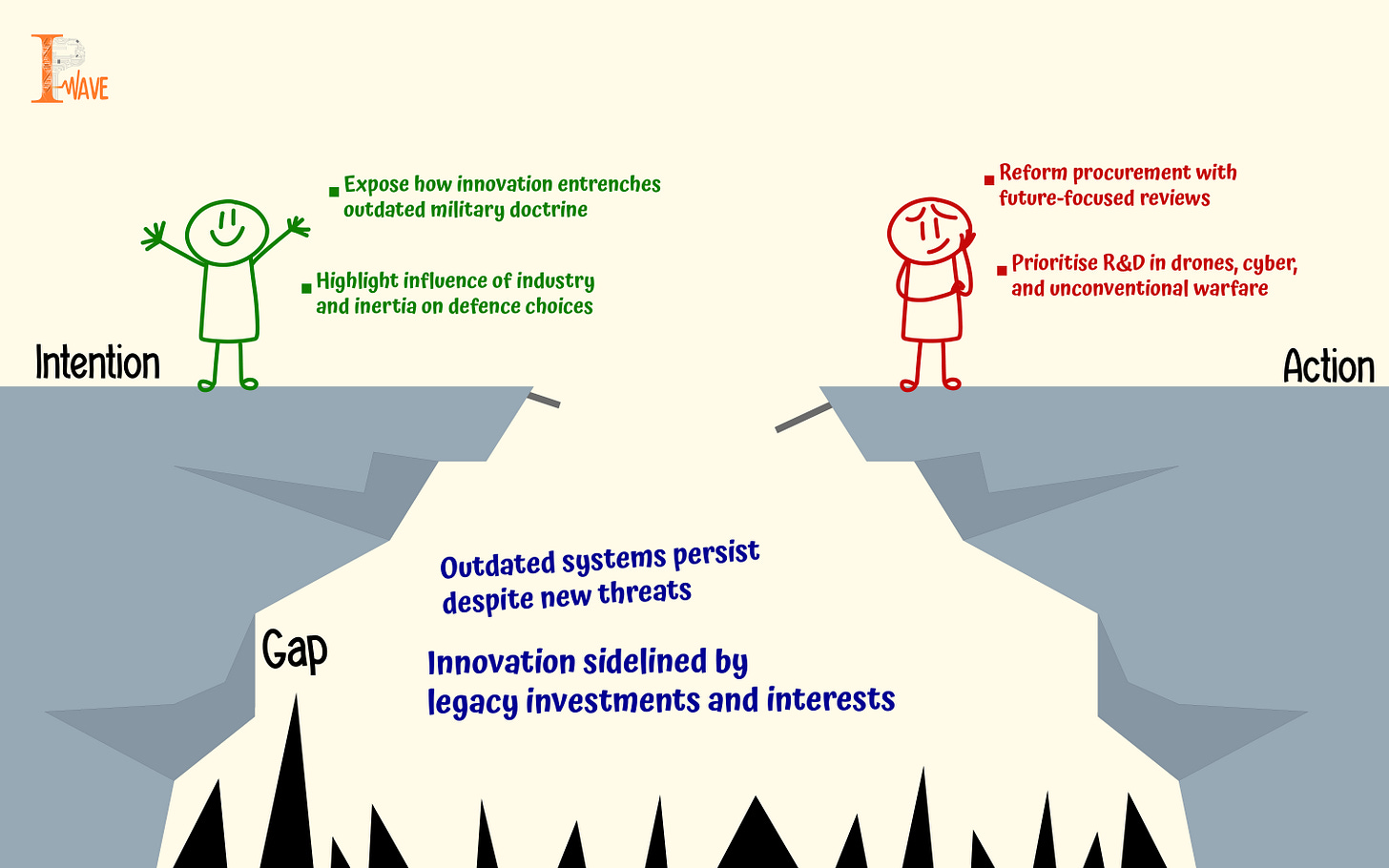

Disrupting the Continuum

The military-industrial cycle is not inevitable but to leave it requires conscious resistance. It requires facilitating strategic assessment, like that of the U.S. "TacAir" study to challenge existing assumptions. It requires setting sensible budgetary practices that do not finance future outlays by tapping into investments in the past. It requires creating a culture that focuses on mission outcomes over platform preservation.

Most importantly, armies must recognize that technology and doctrine co-develop. Acquiring drones or cyber assets is not a procurement decision — it's a wager on reimagining warfare. If that change doesn't occur, states risk gearing up to fight yesterday's wars with yesterday's tools, trapped in a vicious spiral of their own making.