Samaki Cookies: How a Fishy Idea Turned Into an Innovative Solution to Malnutrition in Kenya

In a world of technological marvels and AI-powered breakthroughs, it’s easy to overlook the quiet revolutions happening at the community level. But sometimes, the most groundbreaking innovations are those born out of necessity, crafted by hand, and driven by empathy. One such story comes from the coast of Kenya, where a sociologist-turned-entrepreneur, Frank Thoya, has created a small cookie with a big mission: fighting malnutrition using the power of locally available products.

A Snack That Solves Real Problems

The Samaki Cookie, named after the Swahili word for "fish," is not your average treat. It combines whole dried fish, cassava flour, groundnuts, cashew nuts, fresh coconut, icing sugar, and margarine into a nutrient-packed snack aimed at pregnant women and malnourished children. While the ingredients may raise eyebrows at first, especially the use of the entire fish, the cookie has defied expectations.

Unlike processed meals or supplements that often involve waste and additives, Thoya’s approach embraces wholeness and locality. Every component of the cookie is sourced from local producers like fishers, coconut vendors, cassava growers making it an ecosystem solution as much as a dietary one. What began as an improvised response to the economic disruption caused by COVID-19 has grown into a multi-dimensional innovation targeting food insecurity, public health, and youth employment in the region.

From Event Planning to Empowered Innovation

Before the pandemic, Frank Thoya was an event planner. With gatherings shut down in 2020, his income vanished. But rather than wait for things to return to normal, Thoya started looking around Kilifi County and saw a different crisis brewing - malnutrition. Especially among children, the lack of affordable, nutritious food options was a silent killer.

He also noticed something else: children had an undying love for snacks. Could he merge the two worlds into something delicious, but also life-saving? It was a question no one else had asked, and certainly not answered with fish.

With no formal training in baking, Thoya relied on trial and error, spending over two years experimenting with different local ingredients. The first few batches were failures, and cassava flour which is a healthier and locally available substitute for wheat proved tricky to work with. But he persisted, eventually arriving at a formula that was not only nutritious and shelf-stable, but also pleasant to the palate.

Nutrition, Community, and Local Economy, All in One Bite

At its core, the Samaki Cookie is a food supplement. According to nutritionists at Pwani University, the cookie is exceptionally high in protein, thanks to the use of whole fish. It addresses micronutrient deficiencies that are common among pregnant women and children, especially in low-income regions. In doing so, it becomes a functional food;the kind of innovation public health experts have long advocated for, but rarely see implemented with such grassroots success.

This innovation also contributes to supply chain resilience. As Thoya rightly points out, fish farmers are often plagued by saturated markets and low demand. By purchasing fish for processing, Samaki Cookies create a new demand stream, allowing producers to monetise their catch even during low seasons.

With support from the YISA programme—a partnership between the Mastercard Foundation and Farm Africa focused on aquaculture and youth employment—Thoya secured a Kenya Bureau of Standards certification, expanded visibility across media outlets, and scaled up production. His business, SeaBerry Snacks, now employs six staff directly and has created dozens of indirect jobs through local sourcing.

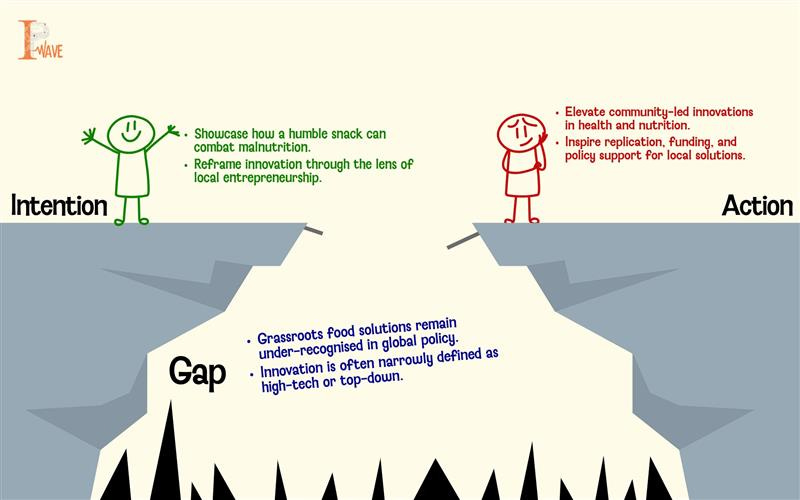

Local Innovation for Global Problems

At a time when malnutrition continues to affect over 800 million people globally, Thoya’s innovation is a powerful reminder that solutions don’t always require complex global aid systems or biotech patents. Sometimes, they come from rethinking what already exists around us.

The genius of Samaki Cookies lies in their simplicity and adaptability. It reimagines undervalued resources (like fish offcuts), uses culturally accepted ingredients, and taps into existing food habits (snacking). In this, it echoes a broader message for development and health policy: if we want to solve hunger, we must first understand what people already eat, what they enjoy, and what they can access.

And perhaps just as importantly, Samaki Cookies prove that innovation doesn’t belong only to engineers and labs. Frank Thoya was a sociologist, not a chef. His idea wasn’t born from algorithms but from a deep understanding of his community’s problems—and a relentless determination to fix them.

A Bigger Vision

Looking ahead, Thoya envisions building a full-scale factory in Kilifi, complete with cold rooms and industrial ovens, employing more youth and improving supply chain infrastructure. His story is a powerful testament to what can happen when entrepreneurship meets empathy, and when local knowledge is treated as a foundation for innovation.

At a time when we debate the ethics of lab-grown meat and AI-enhanced agriculture, perhaps it’s worth pausing and asking: what other magic might we find in fish, cassava, and peanuts?

Sometimes, the future of innovation isn’t about inventing new materials. It’s about seeing the extraordinary potential in the ordinary.

Fish cookie, anyone?