Piracy, Paywalls, and the Price of Watching Sport

On the eve of the 2025 IPL season, the Delhi High Court issued a sweeping order to block dozens of “rogue websites” illegally streaming matches. Calling it a case of “systematic, organised and intentional” copyright violation, the Court granted a ‘dynamic+’ injunction in favour of Star India, allowing enforcement to respond in real time as new infringing URLs emerged. “Hydra-headed,” the Court called them—pirate sites that use identity-masking, URL redirection and rapid duplication to stay one step ahead of IP enforcement.

This is now standard practice during major Indian sporting events, from the IPL to the Women’s Premier League. While platforms like JioCinema previously offered free IPL streaming, the 2025 season has shifted to a subscription-based model—albeit often bundled with telecom data plans. Still, the same level of access and affordability is not available for many international leagues or tournaments. And yet, despite widespread enforcement efforts and increasingly sophisticated digital takedowns, illegal streaming continues to flourish.

To understand why, one need only look at the strange case of Amazon’s Fire Stick.

In India, Fire Stick devices are legal and widely used, often with subscriptions to platforms like JioHotstar, SonyLIV and others that hold rights to everything from cricket and kabaddi to European football. Indian viewers can, in fact, watch every single Premier League match as part of a paid digital package. Ironically, fans in the UK—where the league is based—cannot do the same. Domestic broadcast restrictions mean not all matches are shown live, and multiple services are needed to follow a single club through the season.

This asymmetry has birthed a phenomenon. Jailbroken Fire Sticks, preloaded with pirated apps, are increasingly common in the UK and across Europe. “Probably about half of the piracy [in the UK] comes from Fire Sticks,” said Sky COO Nick Herm at the FT Business of Football Summit, noting that fans had even begun chanting “We’ve got our Fire Sticks” in stadiums. Shirts printed with the phrase have become a kind of anti-paywall protest, a cheeky reminder of how easy it is to sidestep the system.

“We’re getting to the stage where it’s almost a crisis for the sports rights industry,” said Tom Burrows, global head of rights at DAZN, the international streaming giant. “Media-rights deals have been done on the basis of exclusivity but… there’s almost an argument to say you can’t get exclusive rights anymore because piracy is so bad.”

From the Delhi High Court to the Premier League’s private prosecutions, the pushback has been forceful. In the UK, a Liverpool man was sentenced to more than three years for selling illegal Fire Sticks and advertising on Facebook. In Belgium, DAZN secured an order to block over 100 pirate sites. And across Europe, platforms like Cloudflare, Google, and Cisco are being forced to comply with IP takedown requests or face massive fines.

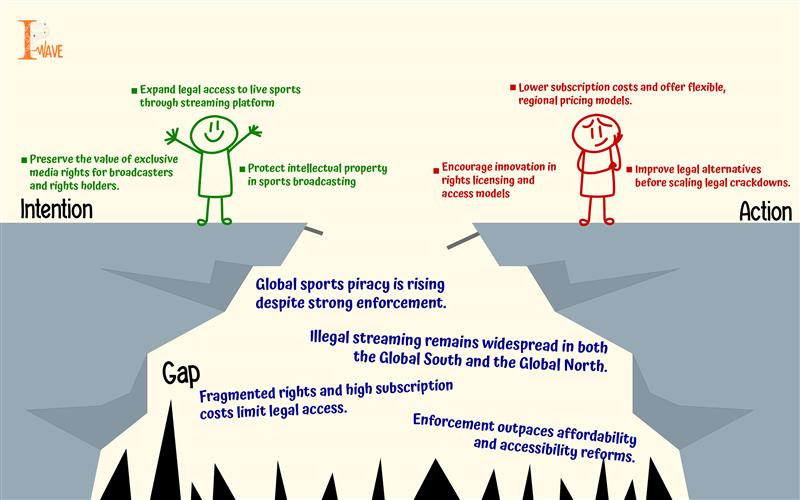

But beyond enforcement lies a more fundamental issue: access.

A recent GlobalData report refers to piracy as “the single biggest threat to the sports media industry,” estimating annual losses at $28.3 billion. But it also acknowledges that cost is a key driver. “The proliferation of platforms with sports spread across them has raised the cost for many of watching the sports in which they are interested,” the report notes. Many fans, especially younger ones, simply cannot afford multiple subscriptions. Where legal options are fragmented, expensive, or unavailable—piracy fills the void.

This is especially true across much of the Global South. In many countries, matches are not broadcast at all. In others, subscription rates are out of sync with local income levels. For these viewers, illegal streaming is less a deliberate violation than a necessity. It enables participation in global cultural moments that would otherwise be inaccessible. Piracy, in this sense, becomes a form of informal democratisation.

Saudi Arabia, too, is paying attention. Through Surj Sports Investment, the kingdom’s Public Investment Fund has taken a minority stake in DAZN and committed $1 billion towards a joint Middle East streaming venture. The goal is to bring more sport to more viewers at lower costs. DAZN will serve as the broadcast partner for Saudi-hosted events and stream the Club World Cup globally, for free, as part of its new FIFA partnership.

Whether this is a genuine attempt to address pricing or part of a broader sportswashing strategy remains debated. But the underlying rationale is clear: if fans are leaving the official ecosystem, the system itself may need to change.

The future of sports IP cannot rest solely on enforcement. Rogue websites will multiply. Jailbroken apps will evolve. And platforms will continue to battle over exclusivity. But if broadcasters want fans to return to legal services, they will need to offer more flexible, affordable, and accessible packages.

Lowering subscription costs, simplifying rights bundles, localising content, and making legal options available in all markets could convert piracy into participation. As the GlobalData report suggests, reducing prices could still “unlock potentially millions in subscription fees”—especially if viewers feel they are no longer being locked out.

Because in the end, this is not just about rights—it’s about the right to watch. Intellectual property protection must be paired with equity. And sport, more than any other domain, reminds us that access isn’t a luxury—it’s the game itself.