Reframing Copyright Act for AI and Digital Education in the Light of DU Photocopy Case

In 2016, within Delhi University, a small photocopy shop found itself at the center of a landmark copyright fight between global publishing giant (Oxford University Press, Cambridge University Press and Taylor and Francis) and the right to education in India. The case, Oxford University Press and Others vs. Rameshwari Photocopy Services & Delhi University, famously known as “DU photocopy case” posed a question that resonates even more today: how to balance IP Rights with affordable access to knowledge?

Delhi High Court’s ruling was welcomed as triumph for public interest and celebrated in the world of education as it upholded the right of students and educators over the claim of publishers. The court held that photocopying extracts from books for educational course packs came under the “fair dealing” exception of India Copyright Law. In a nation where education is regarded as a right, IP cannot be protected on grounds that leave major segments of the public behind.

Jump to present times, the battlefield has changed from photocopy stores to online platforms, AI chatbots and online learning tools based on machine learning and algorithms. The question remains the same, who owns these educational contents, and how freely can or should it be accessed?

Academic publishing is becoming increasingly subscription based, platform dominated, where access is based on institutional buying power instead of academic requirement. In a country where university fees are a fraction of what students pay in developed nations, expecting them to buy multiple high priced international textbooks will be unrealistic. The OUP v. DU case brought into sight that strict application of copyright can be at odds with the realities of education in resource constrained environments.

Previously publishers would worry about course packs eating their textbook revenues, now they have much bigger problems. Large digital libraries and AI systems can summarise, paraphrase and produce textbook like content without spending even Rs 1 in licensing fees. Students and educators have moved away from printed course packs towards using platforms like SWAYAM (over 46 million students enrolled till date) and Coursera (28 million registered users as of December 2024), and even generative AI to access and explain complex academic concepts.

AI systems are based in huge text databases, including scholarly literatures, which threatens the very foundation of copyright law. Publishers argue that unauthorised text mining and data scraping for AI training constitute serious large-scale infringement. Whereas innovators of these AI and educators counter that these technologies democratise access by dismantling long enforced barriers of paywalls.

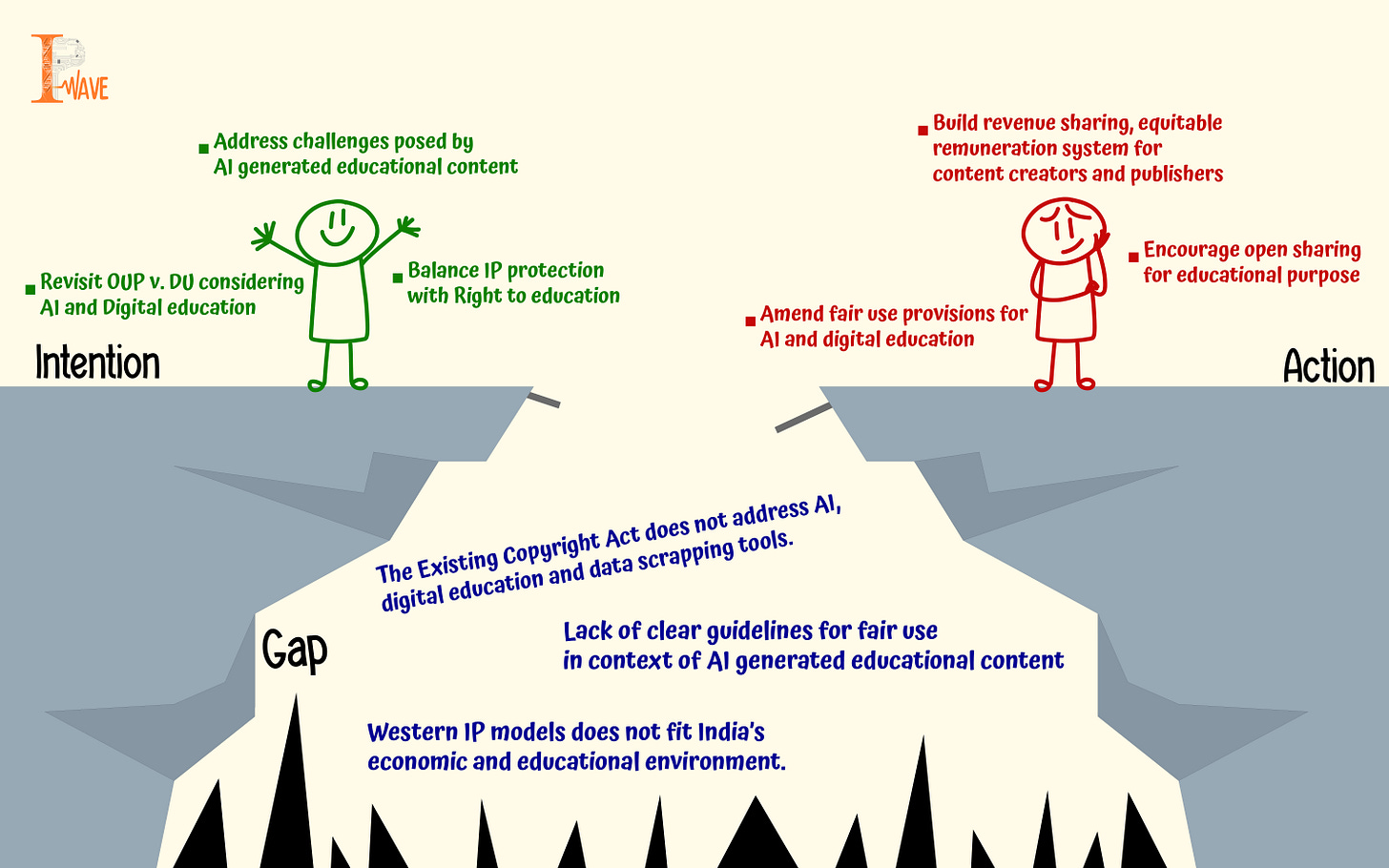

India is at a delicate juncture. On one hand, the government’s National Education Policy (NEP) envisions increased open access and equal education and thus IP enforcement cannot be ignored. Globally, there is growing pressure on India to strengthen its copyright laws to Western standard. However, implementing Western models of copyright in the country might not be a good idea as it has specific educational and economic conditions which cannot be overlooked.

The photocopier was the villain in 2016, in 2025, it is the AI and data scraping software. The essence of these conflicts is identical with the OUP v. DU debate. Should knowledge that serves public educational objectives be locked away behind strict pay models, or can it be accessed freely under fair use? The case was not just about photocopies alone, it was about who owns knowledge, under what terms, and at what price. Education is not a commodity in the marketplace but a public good. The law has to change to safeguard creativity without undermining access.

AI offers a chance for India to rethink copyright exceptions and fair use provisions. Rather than setting up AI as an existence threatening problem, publishers and policymakers can look at mechanisms for revenue sharing, equitable remuneration for content creators, and open access requirements.