Labubu Mania: Rise of China’s Creative Economy

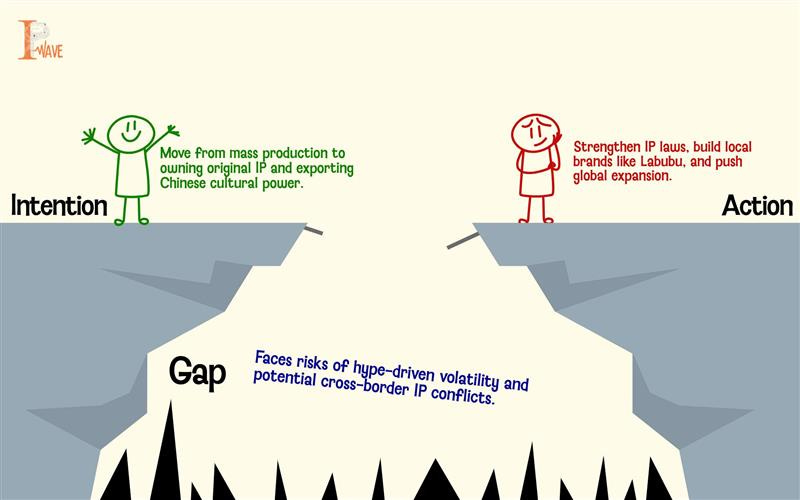

China had long been viewed as a country that had no intention of establishing its unique footprint in creating original goods, a home to mass production but lacking its own ingenuity. Yet, in recent times we have seen a change in China’s approach, a renewed focus on developing its own products rather than being reliant on Western creativity and technology.

China has also seen a recent slew of Chinese products receive global recognition, such as the original Chinese blockbuster game Black Myth: Wukong, which showcased Chinese heritage and culture, and the TikTok alternative Xiaohongshu, a hugely popular social media app in China. Similarly, Labubu, the quirky designer toy, has sent collectors and young shoppers across Asia into a frenzy.

Labubu, the brainchild of Hong Kong artist Kasing Lung and brought to the public by Chinese toy giant Pop Mart, has unexpectedly proved more successful as a cultural export than many of the country’s heavily backed showcases. What began as a niche designer figure has exploded into a phenomenon with long queues, speculative resale markets, and even viral dance videos. In June 2024, a human-sized Labubu doll sold in Beijing for around 1.08 million yuan (about US $150,000), underlining just how far the craze has spread. While the character’s mischievous grin and elfin features seem innocent enough, Labubu’s true significance lies in what it represents: China’s strategic move from manufacturing others’ ideas to creating and owning its own intellectual property.

Pop Mart, which introduced Labubu to the mainstream, has mastered the "blind box" model, selling sealed packages where buyers do not know which character they will receive. This mix of surprise, scarcity, and collectability has proved irresistible to China’s Gen Z consumers, who crave novelty and social currency as much as physical products. Rare editions of Labubu have sold for many times their original price on resale platforms, echoing global sneaker hype or limited-edition streetwear drops. In 2024 alone, Pop Mart’s total revenue surged to RMB 13.04 billion (about US $1.8 billion), with Labubu accounting for roughly RMB 3.04 billion — an astonishing 727% year-on-year increase.

Behind this success is a deliberate shift in China’s approach to IP. Once content to produce toys for global giants like Disney or Marvel, Chinese companies are now aggressively building their own IP portfolios. Pop Mart has filed hundreds of trademarks and design patents to protect its characters, signalling a new era where IP ownership is central to growth. This pivot is not just about higher margins. It is also about cultural soft power: shaping global tastes and exporting Chinese creativity. China’s policymakers have played a crucial role in enabling this transformation. Stronger copyright and trademark laws, coupled with more rigorous enforcement, have given domestic creators the confidence to invest in original design. Government-backed programmes encourage cultural exports and celebrate local design talent, further embedding IP creation into the national economic agenda.

Pop Mart’s journey highlights this evolution. Listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2020, the company quickly became a darling of investors and today has grown into a global powerhouse valued at around US $40 billion. Labubu and its peers have turned Wang Ning, Pop Mart’s founder, into one of China’s youngest billionaires, with a net worth now estimated at over US $22 billion. His fortune has grown so rapidly that at one point, he added US $1.6 billion in a single day due to Labubu’s runaway popularity.

The global impact is already being felt. Japanese and American character giants like Sanrio and Funko, once unrivalled in this space, now face serious competition from Chinese creations. Labubu dolls have begun appearing in overseas markets, and Pop Mart has opened flagship stores in cities from Tokyo to Los Angeles. This global push is as much about brand storytelling as it is about sales. By weaving local folklore, subcultural aesthetics, and playful design, these characters appeal to a generation that values authenticity and emotional connection.

Yet, this success story is not without its complexities. The hype-driven model, where scarcity and speculation inflate value, can fuel excessive consumerism and market volatility. Moreover, as Chinese IP begins to assert itself globally, it raises questions about future conflicts over character designs, licensing agreements, and cultural appropriation. Will we see a wave of cross-border IP disputes as Chinese brands protect their creations more aggressively? And how will traditional powerhouses respond when their markets and iconographies are challenged?

China’s creative economy is in a period of boom, which has long been in the making due to its meticulous planning in shifting from just producers to creators. Labubu, with its impish charm and staggering sales figures, embodies this shift better than any policy paper or trade statistic ever could.