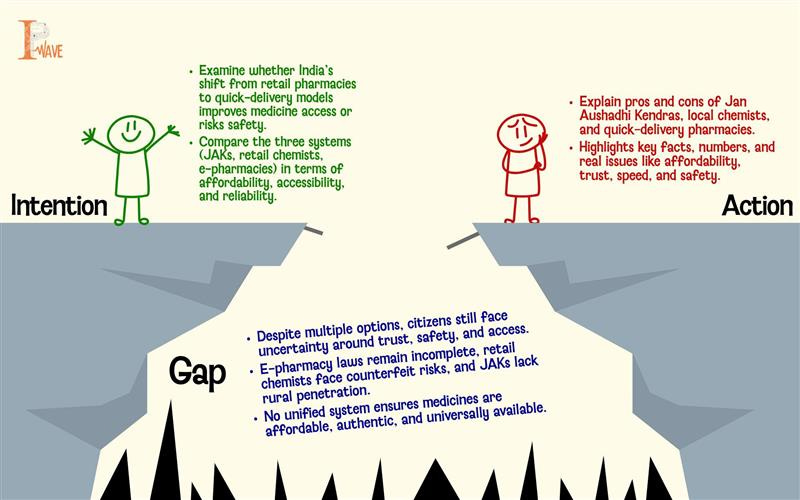

From Retail stores to Quick Delivery: Are Indian Pharmacies Expanding Access or Risking Safety??

India is often called the “pharmacy of the world.” With a massive generics industry that supplies nearly 20% of the world’s medicines, over 10,000 manufacturing facilities, and exports spanning 200 countries. However up to 8-10% of drugs in India may be substandard, with some research indicating that up to 30% of generic drugs sold in less regulated channels. It could be a cough syrup or a painkiller that is ineffective or substandard. Yet, for Indian citizens, an everyday dilemma persists:

Where should I buy my medicines from the government’s Jan Aushadhi Kendras, my trusted local chemist, or the quick delivery apps?

Jan Aushadhi Kendras: Affordable but Not Everywhere

India has expanded to 16,912 Jan Aushadhi Kendras with a stock 2,100+ generic medicines and 315 surgical items, spanning most major therapeutic groups like paracetamol, diclofenac, ciprofloxacin, cetirizine and essential cough syrups are widely available. Generic medicines are affordable to all, as they are sold at 50–80% lower prices compared to branded versions. In fact, the government estimates citizens have saved ₹30,000 crore over a decade through Jan Aushadhi pharmacies.

The JAK supplies are regulated and sourced centrally, tested under CDSCO/DoP guidelines, and distributed via monitored warehouses. This means better protection against counterfeit or substandard drugs that sometimes slip into unregulated supply chains.

Despite the numbers, many parts of India particularly remote villages still don’t have a nearby Kendra. They experience stock outs and delivery delays very often due to a very limited basket of medicines and supply chain issues. This sometimes led to lack of convenience for citizens and making retail shops and online platforms more appealing and accessible.

JAKs guarantee affordability, but not universal reliability.

Local Chemists: Trusted but Inconsistent

Local chemist has been India’s go-to healthcare provider, often play dual roles as an informal medical advisor when doctors aren’t easily accessible and affordable. These chemists are licensed and regulated under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 and the Pharmacy Act, 1948. For a large majority of citizens (mainly who are not tech savvy), trusting a chemist they have known for years feels safer and trustworthy than uploading prescriptions to an app digitally.

However, it also has systemic weaknesses such as supply consistency varies widely. Smaller chemist shops often don’t stock less-common or chronic drugs due to limited capacity. Although, the recent reform in 2025 are tightening regulations for more stringent Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) and traceability, however compliance across millions of retailers will take time.

Quick Delivery Pharmacies: Fast but Fragile

The availability of generic medicines is rising rapidly not only through Jan Aushadhi Kendras, retail pharmacies but increasingly through quick commerce platforms partnered with e-pharmacies (e.g., Swiggy with PharmEasy, Tata 1mg with BigBasket) targeting fast delivery, including medicines with prescriptions in select cities. These platforms are gaining attraction, contributing about 2%–3% of total medicine sales in India a present. For urban Indians, these platforms make it easier and convenient to order medicines online, get them home-delivered, sometimes in 1-2 hours. The progress is huge, from $0.5 billion market in 2019, e-pharmacies have already grown to $4.5 billion by 2025, it will rise to 15% of India’s medicine sales over the next decade. The comfort of doorstep delivery is unmatchable to going to retail shops or Kendra’s for India’s working population and patients with some illness

However, the quick delivery service also has a regulatory grey zone. India still has no finalized e-pharmacy law. Draft rules introduced in 2018 (requiring registration with CDSCO) are pending, which means the online players operate in a no legal space.

Misuse of prescriptions such as uploaded prescription multiple times, enabling attempts at drug abuse. Identity verification is weak, and minors could technically order restricted medicines. There are no quality checks, a compliance review found none of India’s top e-pharmacies fully met regulatory requirements or registration. And most importantly, the rural citizens and less tech-savvy patients remain out of reach, deepening healthcare inequity.

Critics highlight risks such as lack of stringent prescription verification, handling of controlled substances, sale of expired or counterfeit medicines, and insufficient supervision by quick commerce platforms. Recently the chemists’ associations (AIOCD) seek to ban these platforms, lobbying aggressively against them. In fact, a 2018 Delhi High Court order briefly banned online pharmacies over fears of unsafe drug sales, highlighting the lingering mistrust.

We have so many options, yet the problem of access has not been solved because each option has its promise and pitfalls.

Jan Aushadhi Kendras → Affordable + verified quality, but not accessible everywhere.

Retail Pharmacies → Accessible and personal, but inconsistent on quality and prone to counterfeit entry.

Quick E-Pharmacies → Convenient and modern, but legally unsteady and sometimes risky for patients.

What India Actually Needs?

The way forward is not about choosing one system over another, but about integration like Indian should adopt hybrid models by collaborating Quick-delivery platforms with Jan Aushadhi stocks to combine affordability with convenience. Retail chemists could also digitize to ensure home delivery but under licensed oversight.

Government needs to tighten uniform quality monitoring whether it’s a JAK, a retail shop, or a pharma app, that every drug sold should be verifiably authentic, tested, and traceable.

Finalize rules on verification, prescription handling, and data privacy. With India’s rapid digital adoption, leaving e-pharmacy in a legal grey zone is risky.

All these platforms are still urban-centric. Without reaching villages, the access remains limited. Thus, integration of all of these is important with pairing JAK affordability and safety, retail reach and trust, and online access and ease, we’ll finally have a delivery system that guarantees all three together.

India’s pharmacies, either government counters, chemists, or digital apps, each play a role. But they don’t want options and choice for the sake of health; they want certainty that when they take a pill, it is genuine, affordable, and available when needed.