Faith, Law, and Monopoly: Can Sacred Terms Belong to One Temple?

The name of a god can unite millions, but can it also be owned? This uneasy question sits at the heart of a recent dispute between Odisha and West Bengal. When a new Jagannath temple opened in Digha in April 2025, it was unveiled as “Jagannath Dham.” For devotees in Odisha, where the 12th-century Puri temple has carried that title for centuries, the announcement felt like a challenge to the shrine’s unique identity. Politicians, priests, and pilgrims rallied around the claim that the phrase belongs only to Puri.

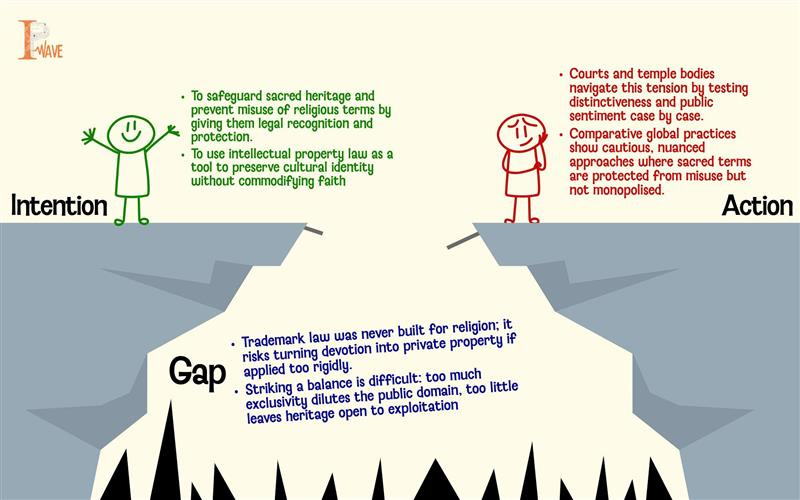

In response, the Shree Jagannath Temple Managing Committee (SJTMC), which manages the Puri shrine, announced plans to trademark a cluster of terms: Shree Jagannath Dham, Srimandir, Mahaprasad, Nilachal Dham, and Bada Danda, along with the temple’s emblem. For the committee, the goal is not commerce but preservation, preventing other bodies from appropriating phrases woven into Puri’s spiritual life. Yet this move presses intellectual property law into territory it was never designed for, raising a central question: can faith itself become a brand?

The IP Framework

Trademark law in India, under the Trade Marks Act, 1999, is built on the principle of distinctiveness. A valid trademark must signal the specific source of goods or services, not simply describe a generic idea. Terms like Mahaprasad or Srimandir are widely used across temples, making them “generic” in the trademark domain. Granting exclusivity would risk what lawyers call genericide, the monopolisation of words that belong to common usage. By contrast, “Shree Jagannath Dham” may arguably function as a badge of origin, because the phrase has become inseparably tied to Puri in the public imagination.

Beyond distinctiveness, Section 9(2)(b) of the Act introduces the safeguard of public sentiment, barring marks “likely to hurt religious susceptibilities.” This clause blurs legal and cultural lines. It requires examiners and courts to look not only at whether a term functions as a trademark but also whether its registration would provoke offence or unrest. This dual test, distinctiveness on one hand and respect for faith on the other, makes cases like Jagannath particularly hard to resolve.

There is also the issue of dilution, a well-recognised concern in trademark law. Famous marks are protected not only against direct copying but against uses that weaken their uniqueness. SJTMC’s argument rests partly on this idea: if multiple temples start calling themselves “Jagannath Dham,” the spiritual and cultural weight of the Puri shrine may be diluted, even if no commercial harm occurs. Here, trademark law offers a tool, but one whose fit with religious heritage remains uneasy.

Courts and the Clash of Principles

Indian jurisprudence reflects the tension between protecting collective heritage and recognising distinctiveness. In Mangalore Ganesh Beedi Works v. District Judge (2005), the Allahabad High Court allowed a bidi manufacturer to use the image of Lord Ganesh, reasoning that such use was not inherently offensive. More than a decade later, in Lal Babu Priyadarshi v. Amritpal Singh (2015), the Supreme Court took a stricter approach, refusing the registration of “Ramayan” as a trademark for incense sticks on the ground that the name of a holy text could not be monopolised. Most recently, in Shyam Steel Industries v. Shyam Sel (2019), the Calcutta High Court reiterated that religious terms are not barred outright; instead, each case must be assessed on distinctiveness and on whether registration would genuinely harm public sentiment.

For Jagannath, these precedents cut both ways. They suggest that SJTMC could secure protection for terms tightly bound to Puri’s identity, but will struggle with generic expressions. They also show that courts are reluctant to impose an absolute rule, preferring case-by-case judgments that balance exclusivity with openness.

Beyond Law: Identity and Global Lessons

Politics has only sharpened the conflict. Odisha leaders insist there is only one Jagannath Dham in the world, while Mamata Banerjee counters that reverence cannot be limited to geography. In such circumstances, trademark registration is not just a legal instrument but a symbolic act of cultural assertion.

Globally, IP law has confronted similar challenges. The US Patent and Trademark Office has blocked registrations of Native American sacred terms, framing them as collective heritage, while allowing some biblical references in clearly commercial settings. The European Union Intellectual Property Office bars religious symbols when their use offends public morality, such as placing crosses on alcohol branding. Thailand permits certain religious marks but restricts their use if deemed disrespectful. Across systems, the guiding theme is caution: intellectual property rights may sometimes protect cultural integrity, but they must never reduce the sacred to the merely commercial.

Drawing the Line

The Jagannath case highlights the clash between two intellectual property principles: protection against dilution and preservation of the public domain. Trademarks can safeguard unique identities, but they can also overreach, turning shared religious expressions into private property. If the law leans too far towards exclusivity, it risks treating devotion as a marketable asset. Refusing protection altogether, however, leaves sacred heritage open to misuse.

The solution, as courts in India and abroad suggest, lies in nuance. Distinctive terms tied closely to one shrine may deserve protection, while generic words of faith must remain free. Trademark law should act less as a tool of ownership and more as a shield against exploitation.

The battle over “Jagannath Dham” is therefore more than a quarrel between two states. It exposes the uneasy fit between intellectual property and the language of faith. Whether SJTMC succeeds or not, the case underscores a truth: in religion, names are never just labels. They carry memory and devotion, and trying to protect them through intellectual property will always remain contested.