Detachment 201: Silicon Valley Goes to War

When the U.S. Army swore in four Silicon Valley tech executives as lieutenant colonels on June 13, 2025, it did more than expand the Reserve roster. It rewrote the rules of military innovation. Dubbed Detachment 201: The Executive Innovation Corps, the initiative has no historical parallel as it embeds top-tier civilian talent into the Army’s ranks. But the inclusion is not as consultants, but as uniformed officers, which blurs the line between software labs and the battlefield.

This move is not symbolic. Andrew Bosworth (CTO, Meta), Kevin Weil (CPO, OpenAI), Shyam Sankar (CTO, Palantir), and Bob McGrew (Thinking Machines Lab) aren’t merely lending advice from a distance. They’ll serve 120 hours a year in uniform, with real assignments related to Army modernisation, from battlefield AI to logistics software. These aren’t field postings, but they’re not figureheads either. This is hybrid service — and it might just be the future of civil-military synergy.

A New Model for Innovation

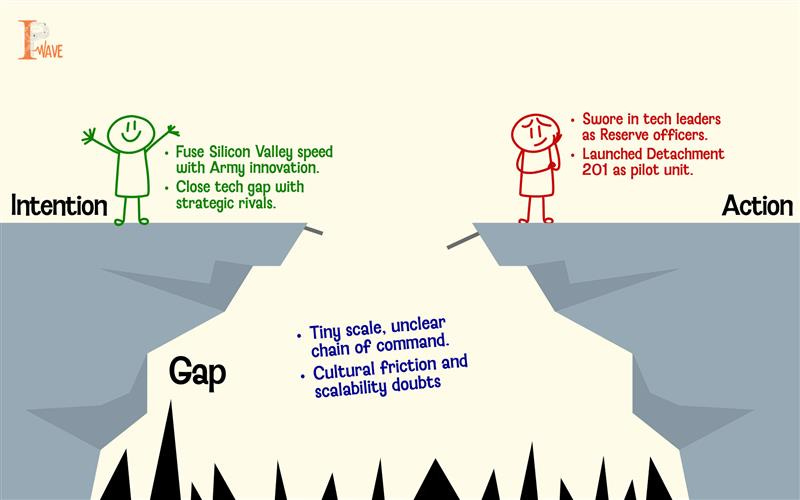

In a world where external contractors and advisory boards have long been the norm, Detachment 201 pushes beyond the traditional model by internalising private-sector talent. Instead of sending projects to Silicon Valley, the Army is bringing Silicon Valley into its chain of command. That’s an institutional bet on agility, experimentation, and cross-pollination with commercial leadership.

And it’s a bet the Pentagon must take. American adversaries like China are rapidly deploying battlefield technologies, from drone swarms to quantum-encrypted communications. America’s military procurement pipeline, which is still somewhat mired in multi-year cycles, is showing its age. Detachment 201 offers a way to fast-track ideas and test them with immediate operational feedback. Bosworth put it bluntly: “We need to go faster. And that’s exactly what we’re doing here.”

Service Without Sacrifice

However, this isn’t conscription. Nor is it about tech bros in camo. These officers will complete physical and marksmanship tests, but their contribution is intellectual. It’s a new form of national service. One that doesn’t demand a career reset. You can lead product at OpenAI and serve your country, all in a calendar year’s side window. That accessibility is precisely what makes it scalable.

By legitimising a hybrid form of public service, Detachment 201 broadens who can serve and how. It signals that patriotism isn’t constrained by traditional uniforms or time commitments. For a generation of tech professionals disillusioned with politics but hungry to make an impact, this is a direct channel to national relevance in the US.

Strategic Implications Far Beyond the U.S.

This development is not just a U.S. initiative; its ripple effects are being felt across allied nations. From the UK to Germany, militaries struggling with stagnant tech adoption may soon mimic this model. Instead of waiting years to reform acquisition policies, they might simply embed the reformers. Indeed, if Detachment 201 succeeds, it could become a template for agile military innovation across NATO and beyond.

This expansion of the model is about more than just bureaucratic efficiency. It’s about strategic advantage. In an age of hybrid warfare, where information dominance can be more decisive than kinetic force, the most effective weapons are often software platforms, not missiles. The question is no longer just how many tanks you have, but how fast your systems can adapt.

Not Without Risks

Of course, this bold move isn’t without its challenges. What happens if a tech officer’s priorities clash with their employer’s commercial interests? Or when the Army needs to demand a pace or output their companies can’t afford to give away? The risk of conflict of interest is real and will require guardrails, from disclosure to operational boundaries.

Then there’s the issue of culture shock. Military organisations run on hierarchy, codified procedure, and discipline. It’s well-known that Silicon Valley thrives on failure tolerance, pivoting, and decentralised decision-making. This collision may produce creative sparks or bureaucratic burnout. If Detachment 201 becomes bloated, directionless, or politicised, it risks becoming the worst of both worlds. One could also see this as the next step in the privatisation of forwarding a state’s core interests.

A Necessary Disruption

But despite the risks, those challenges might be exactly what the defence world needs. For too long, innovation has been flirted with without a full embrace. Initiatives often get stalled by red tape or misalignment between engineers and end-users. Detachment 201 places those engineers next to the end-users literally and gives them a stake in the outcome. That’s not just smart. It’s overdue.

As the nature of warfare evolves, so too must the institutions that equip the warfighter. The modern soldier isn’t just carrying a rifle. They’re operating in networks, navigating drone swarms, and outwitting AI-powered adversaries. The systems that support them must adapt accordingly or risk becoming irrelevant.

Conclusion

Detachment 201 is a strategic gamble that challenges old assumptions about national service, innovation, and civil-military collaboration. It tests whether part-time officers can make a full-time impact and whether democracies can out-innovate other political systems by unlocking their greatest asset: civilian ingenuity.

If it works, it could redefine the nature of service, inject fresh lifeblood into aging bureaucracies, and provide the U.S. military with the one edge that’s hard to match: brainpower in uniform.