China’s Driverless Playbook Is Beating America’s Patchwork

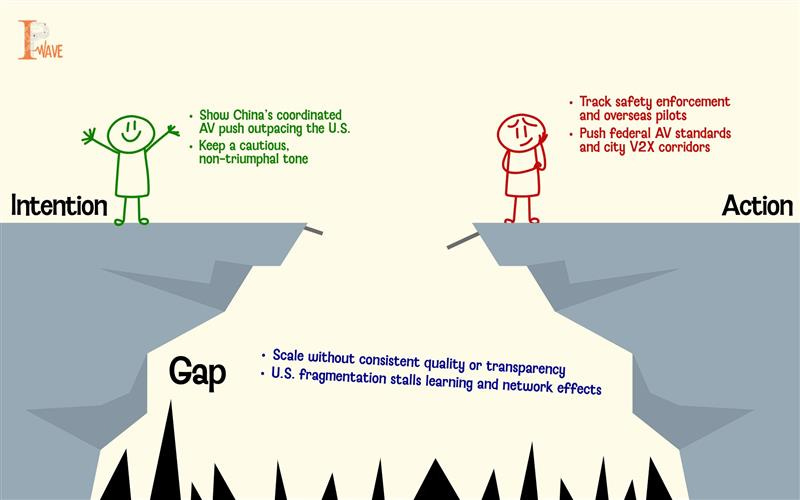

Want to see the future of city streets? You might book a ride in Wuhan at rush hour rather than Phoenix at noon. In China, robotaxis are quietly slipping into everyday life, while the expected leader in the field, the United States, is still arguing over lane markings. It is tempting to declare a winner. Yet the picture is messier up close, and any lead may prove provisional.

Scale, Not Just Showpieces

China now runs robotaxi services from Baidu, Pony.ai, WeRide, AutoX and others in dozens of cities. Many new cars come with Level 2 driver assistance, which can steer and control speed on certain roads but still needs a human in charge. Waymo remains a technical leader in the United States and is adding cities carefully. Even so, China appears ahead on simple scale: more vehicles on the road, larger areas open for testing, and more people riding each day. More miles mean more data. More data means faster improvement, better handling of odd situations, and growing public comfort with computer-driven rides. Scale, however, is not the same as consistency. Big numbers can hide uneven quality, and a polished pilot zone does not always translate into reliable service across a whole city.

Policy Coherence and Infrastructure

China’s edge seems to begin with the rulebook. National and municipal authorities treat autonomous vehicles as a strategic industry. City governments carve out large, contiguous intelligent connected vehicle zones, publish clearer liability rules and streamline permits. Shenzhen’s early regulations became a template others could adapt, which reduced uncertainty for anyone investing in sensors, maps and fleet depots.

Autonomy is also paired with public-realm upgrades. Vehicle-to-everything roadside units, dependable telecoms, smart signals and defined pick up bays may sound prosaic, yet this is the concrete that lets software scale. In China, you can drive far from the big coastal hubs and usually keep a data connection. That reliability shortens the distance between laboratory performance and street performance. By contrast, the United States still works through a patchwork of state laws and city experiments, with federal standards lagging. Operators often win permission one jurisdiction at a time, then defend it in council chambers and courtrooms. Fragmentation slows deployment and blunts network effects. Even so, a slower, more adversarial process can surface risks earlier, and some American cities are building thoughtful playbooks of their own.

Regulators in China have also shown they will pull the brake. After a high profile crash involving a consumer car with advanced assistance, advertising claims were tightened and driver monitoring requirements hardened. Officials still aim to resume approvals for more capable systems on a defined timetable, but with a firmer safety spine. It is a promising balance, although consistent enforcement will matter more than the wording of the rules.

Demand, Data and the Flywheel

Autonomy is not only about algorithms. It is also about the market that absorbs them. Chinese consumers appear more comfortable with AI in the car, and the mobility mix leans toward ride hailing, delivery and bus rapid transit rather than universal private ownership. Fleets value utilisation, uptime and predictable routes, which suits autonomy’s economics. Yet enthusiasm can cool quickly after incidents, and public trust is easier to dent than rebuild.

Chinese technology firms are deeply embedded in the daily digital lives of users, which makes the car the next device in a familiar ecosystem. Xiaomi can sell a sedan that talks to your phone, your home and your payment wallet. Huawei supplies software, sensors and cockpits. Alibaba partners on cloud capacity for training and storage. More connected vehicles mean more driving data, which in turn improves models and ride quality, which attracts more riders. That is the flywheel. At the same time, looser data rules that help the flywheel spin may raise legitimate privacy concerns, particularly as vehicles collect information about streets and bystanders who never opted in.

The Export Test and What Comes Next

The next stage is a test of credibility abroad. Chinese operators are already planting flags in the Gulf and Southeast Asia, often in partnership with local authorities or global platforms. These are not weekend demos. They are routes, depots, maintenance contracts and service level agreements. If China can demonstrate consistent safety enforcement at home, those rules become a sales pitch overseas. If it cannot, hesitation from foreign regulators will grow.

Three questions will decide whether China’s early lead becomes a durable advantage. First, can safety regimes function like export licences, with transparent incident reporting, enforceable driver monitoring and clear thresholds for moving from supervised to unsupervised operation? Second, will city-to-city alliances accelerate diffusion, allowing mayors to buy a full stack rather than a single pilot? Third, can the unit economics close? Costs should fall as domestic suppliers scale lidar, compute and batteries, but profitability still depends on high utilisation and low downtime. China’s dense urban corridors give operators a head start, though not a guarantee.

The United States still has strengths that matter. Waymo’s validation culture runs deep, and American safety science remains a powerful moat. If Washington wants to narrow the adoption gap, it likely needs federal performance standards for autonomous operation, targeted funding for vehicle-to-everything corridors and shared, open datasets that let cities learn from each other. Without that coordination, the next global mobility stack could be built where rules, roads and data pull in the same direction. For now, that place looks like China, though the road ahead remains uncertain.