Bihar ki Baat or Baat Bihar Ki? The Prashant Kishor Case

In India, alongside ballots, branding has become equally important in elections. Campaigns are built on slogans, jingles and logos that can inspire trust or resentment in a matter of seconds. But what happens when one political party accuses the other of stealing their campaign slogan?

That’s exactly the kind of predicament political strategist now-turned politician Prashant Kishor found himself in. What started out as a series of allegations of slogan and content theft changed into India’s first court case of copyright infringement in the political arena.

In early 2020, Shashwat Gautam, a former national data coordinator for the Indian National Congress, accused Kishor of stealing a slogan, logo and data that he had created for the Bihar Assembly elections later in that year. Gautam alleged that one of his colleagues had stolen his laptop that contained details of his Bihar Assembly elections campaign plan called “Bihar ki Baat”. Shortly after the colleague’s disappearance, Kishore announced “Baat Bihar ki” at a press conference in Patna.

The similarity was not coincidental for Gautam. He valued his alleged loss at Rs.10 crore and registered a copyright violation case in Patna alleging theft, breach of trust and fraud. Kishor in response dismissed the allegations as “third rate mischief” and a poor attempt by Gautam to gain attention and called upon the law enforcement agencies for an investigation.

The example that this case could set in the legal arena was much more important despite it having political overtones.

Legal Framework: Intellectual Property Rights in India

India has three main legal tools that could apply to this case. First is the Copyright Act of 1957 which protects original literary works. If slogans are able to demonstrate sufficient originality they can be covered, although courts have been skeptical of short, simple phrases as it would monopolise language that is publicly used. Copyright claims, in the legal sense, do not protect basic ideas or commonly used words. If every catchy small phrase is protected by the law, it would limit free speech and the ability of other political parties to freely engage in political discussions. The Trademarks Act of 1999 is the second legal tool that can be used in this case. Parties can use this Act by registering their campaign tools like slogans to identify and differentiate between campaigns. For example, “Make America Great Again”, the slogan used by Donald Trump is trademarked. Finally, Gautam also used the provisions of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), filing charges of cheating, forgery, breach of trust and conspiracy. The usage of these frameworks led to the case in the area of criminal law.

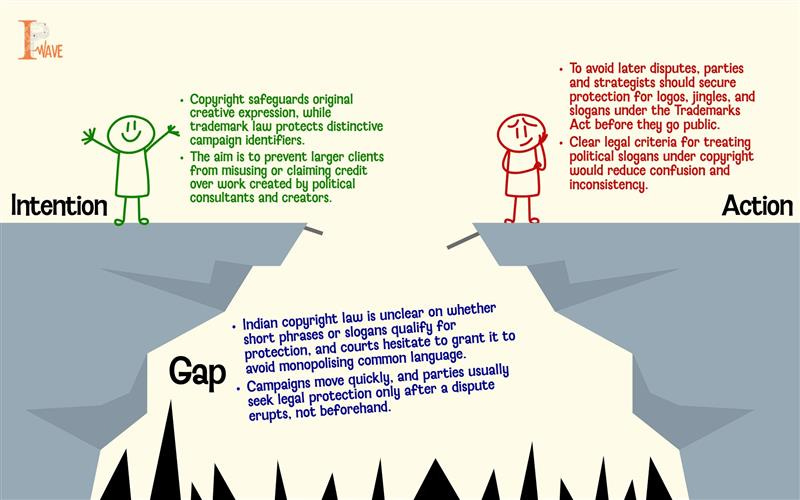

The tension lies in the fact that India’s intellectual property framework was not designed with politics in mind. While slogans that are used by corporations and private firms are secured and protected, political slogans are still ambiguous.

Legal Developments in the Case

The dispute escalated and reached the court of law. A complaint was filed in the Chief Judicial Magistrate’s Court in Patna which was later transferred to another magistrate. An FIR was also registered at Patliputra police station under multiple IPC sections. Even though Kishor denied wrongdoing on his part, Gautam’s complaint was taken seriously and led to multiple procedural steps. Kishor’s request for an anticipatory bail was deferred and was transferred to the Sessions Court. Another Patna court rejected his bail plea in the content theft case.

Even though the case attracted significant media and public attention, there has not been any final verdict. This case blurred the lines between electoral politics and intellectual property law, hence making it a first of its kind.

Why This Case Matters

This was not just a power struggle between Kishor and Gautam. Indian law’s readiness to recognise political messaging as intellectual property was put to test through this case. Due to this test, a number of actors involved in campaigns would be protected in the future. Judicial recognition would lead to safeguarding of work done by creators and consultants from clients who may misuse work without any credit. Political parties would realise that original ideas would be required legally and not just during campaigns. Lastly, the courts would consider if campaign slogans should be protected by law.

There was no denying this case’s symbolic significance. It was described as India’s first political slogan copyright case by media channels and reports. This case brought to light the issue’s uniqueness and lack of established precedence.

Has Branding Become Political?

Along with ideologies and manifestos, branding has become an extremely important tool in campaigns and through slogans and logos public sentiment is captured. Political consultants are acting more and more like marketing agencies, designing and testing slogans. In an environment which is so competitive and fierce, allegations and disputes are bound to arise. Slogans that can influence and tilt entire elections do not enjoy the same protection as jingles and taglines for corporate brands. However, campaigns all over the world have recognised this need for legal protection. Barack Obama’s 2008 “Yes We Can” was trademarked and Donald Trump’s “MAGA” are sold across the United States. Intellectual property protection laws are an afterthought for Indian courts, one that arises only after a dispute emerges.

This case is also important for political strategists and the need to raise their awareness about treating campaign tools such as slogans, logos and jingles as intellectual property and seeking legal protection for them. It also highlights the ambiguity in India’s legal framework which does not provide clear instructions on how short political slogans ought to be treated under copyright law. Political parties must be professional in the way in which they approach intellectual property, just like they manage media and finance.

Not Just a Political Dispute

Although the Kishor-Gautam case may seem like a small political argument garnering media attention, it brings to notice the intersection between intellectual property and politics. The difficulty is determining what counts as authentic and what is public language.

No matter which way the verdict swings, this case has made significant progress by addressing the issue of intellectual property in the electoral arena. It serves as a reminder that campaign tools are not only important in speeches or manifestos but also in courtrooms.

Dear Readers,

After four meaningful years, we have decided to bring the IP Wave newsletter to a close. Your support, engagement, and encouragement throughout this journey have meant a great deal to us, and we are truly grateful to everyone who has been part of it.

However, this is not the end, but a transition.

We are pleased to share that we will soon be launching a new online journal under the IP Wave banner. This next chapter will allow us to build on what we began, with a broader vision and deeper engagement with the intellectual property community. We will be sharing further details very soon.

Thank you once again for being with us so far. We look forward to continuing the journey with you in this new format.

Warm regards,

Team IP Wave