Bad Maps & Big Losses: How India’s Geospatial Gaps Are Breaking E-Commerce

One afternoon, despite our office being just metres from a ‘10-minute delivery’ warehouse, I found myself on a long call guiding a lost delivery agent through mislabelled lanes. That same day, my roommate missed a class waiting for a package routed straight into a 15-foot wall. As we shared these stories over chai, another confused delivery partner arrived, phone in hand, map spinning uselessly. It wasn’t just a one-off glitch—it was a pattern. A deeper failure hidden in plain sight: the silent crisis of bad maps.

The High Stakes of the Last Mile

The last mile, the final step of delivery to a consumer’s doorstep, is both the shortest and the most expensive part of the logistics chain. In India, where addresses are often hyper-local and vague (“second right after the peepal tree, near the small temple”), mapping precision is not optional—it’s essential. Yet, many e-commerce giants still rely on consumer-grade maps meant for general use, which often lack key details like parking spots, entry gates, or even entire buildings in dense or unplanned areas. As delivery partners circle neighbourhoods, making repeated calls and failing to find exact addresses, operational costs soar, customer satisfaction drops, and brand reputations suffer.

Why don’t we have better maps?

One might begin to answer this by looking at India’s restrictive geospatial laws. Mapping in India for decades was the domain of state actors like Survey of India and ISRO. Laws such as the Official Secrets Act, 1923, restricting access to geospatial data. Despite the 2021 Geospatial Data Guidelines liberalising access to some extent, bureaucratic ambiguity and data-sharing hesitancy persist, keeping India’s maps far less accurate and detailed than global standards.

Civilian access to high-access high-resolution satellite data was capped at 1-meter ground spatial distance (GSD). Fine imagery is rendered off due to security concerns. The border zones or ‘sensitive’ areas face even stricter mapping restrictions. In contrast countries, like the United States allow private companies to operate sub-meter-resolution which enables sharp and real-time mapping.

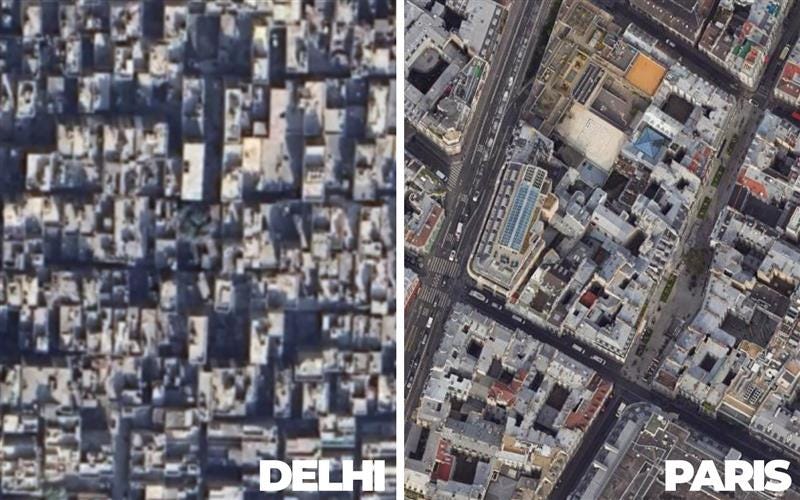

Companies like Google use aerial imaging via aircraft in most urban areas for detailed maps. India prohibits aerial imaging. This means the Indian cities remain frustratingly blurry while the global platforms display ultra-clear visuals in cities like Paris or Austin.

But the problem goes deeper than just outdated regulation. There is a fundamental lack of understanding within policy circles about how these restrictions choke innovation and investment. Geospatial mapping, when viewed purely through a geopolitical or security lens, often sidelines its critical role in fuelling logistics, urban planning, and emerging tech sectors. This reflects a larger strategic trade-off that countries like India face—between asserting control and enabling competitiveness. Unfortunately, India too often chooses the anti-innovation stance, sacrificing digital dynamism for centralised oversight.

Economic and Human Costs

Bad maps disrupt the entire e-commerce value chain. Delivery partners face wasted fuel, lower earnings, mental stress, safety risks, and high attrition. Customers endure delays, missed deliveries, and intrusive calls. For companies, poor mapping raises operational costs, drives customer loss, and blocks expansion into underserved zones—40–50% of which remain unmapped even in India’s most connected cities, stalling growth and frustrating all stakeholders.

In addition to the estimated annual losses of $10–14 billion due to poor addressing systems in India, studies have shown that the last-mile delivery costs in the country account for approximately 35% of the total logistics expenses, significantly higher than the 10–12% observed in Western nations. This disparity underscores the substantial financial burden that inefficient addressing places on India's logistics and e-commerce sectors.

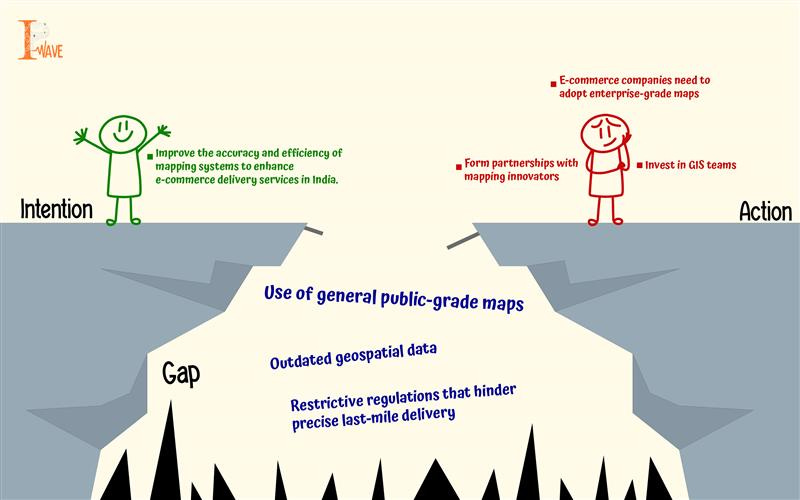

From Consumer Maps to Enterprise Solutions

India’s digital economy urgently needs enterprise-grade maps built for logistics, with hyper-local data like gate timings, road width, and entrances. While companies like Mappls and Genesys offer such solutions, adoption is slow due to high costs and regulatory inertia. Bridging this gap requires investment in GIS (Geographic Information Systems) teams, collaboration with innovators, and policy reforms to unlock mapping potential.

Newer forms of policy intervention must mandate open, interoperable digital addressing systems like Robocodes, that municipal bodies can locally manage and integrate into urban planning, emergency response, and service delivery frameworks. For example, if a city like Dhule adopts Robocodes, local authorities could generate and maintain street-level codes based on evolving layouts, enabling faster ambulance routing or door-to-door public service access without relying on costly, proprietary platforms.

The Bigger Strategic Picture

This concern is not only limited to customer service or convenience. It is a question of national competitiveness. As drone deliveries, autonomous navigation especially in the booming EV sector, and ‘smart city’ infrastructure gain momentum, India’s geospatial lag will become a strategic liability. Already, defence modernisation and disaster management operations suffer due to fragmented or low-resolution mapping.

If India aspires to be a global e-commerce hub and a digital-first economy, then its geospatial infrastructure must match its ambitions.

Conclusion

Maps are far more than just lines and landmarks, they’re the invisible infrastructure behind every smooth delivery and ride. As customer expectations soar and business margins shrink, bad maps aren’t just a minor hassle—they’re a billion-dollar liability. It’s time Indian businesses and policymakers recognised maps not as background utilities, but as critical business assets. After all, in the race to win customer trust and loyalty, the toughest challenge may be finding the most direct route to their doorstep.