IP Wave This Saturday: How India’s Flash Sales Deceive Millions

“80% off”, “Only 2 Left”, and “Buy 2 +1 free.”

Sale season is here again. Flooding our screens with multiple notifications. Urging all of us to buy this season’s most popular item at allegedly affordable price. However, all that glitters isn’t gold and flash sales are worth even less.

A recent report "Prime[D] to Buy: Flash Sales & Deceptive Design" from the Advanced Study Institute of Asia found that most discounts are inflated by over 100% on average. The prices also differ; a water bottle on Apple’s iPhone is costlier than your Android mobile by 12% on average. And all the major apps used deceptive design—design tricks to get people to take certain actions.

So, How does it all work?

Economics of Flash sales:

From an economic standpoint, Flash sales, epitomised by events like Flipkart’s "Big Billion Days" or Amazon’s "Great Indian Shopping Festival," have greatly impacted the e-commerce. These promotional events offer heavy discounts, and exclusive deals, which make us spend. India’s consumer driven economy depends on these sales.

From the company’s perspective, it’s brilliant. Flash sales not only offload inventory but also increase website traffic, boost revenue, and acquire new customers. Flash sales use an economic concept called price discrimination at core. Popularised by economist Arthur Pigou, this idea lets businesses charge varied rates depending on a customer's capacity to pay. Although this is typical in physical markets, e-commerce sites, armed with mountains of customer data, have exasperated it. They maximise income by real-time pricing optimisation, therefore creating the impression of an unmissable offer. Additionally, collaborations with banks and digital wallets offering cashback and EMI options drive sales further, increasing consumer purchasing power. For instance, Flipkart’s 2016 Big Billion Days sale generated ₹3,000 crore in just five days, selling 15.5 million units. That’s the power of consumer psychology and clever economics in action.

For consumers, the economic benefit is murkier. While they may save on specific items, the tendency to extend purchases from needs to wants often results in strained purchasing power and unnecessary financial burdens. Recent data by RBI highlights that there is a 13% increase in credit card use in October 2024.

How They Decieve:

Flash sales are built on the psychology of scarcity and urgency. Noisier landing pages of websites with words like “Only 2 Left” or “80% Off” trigger FOMO (fear of missing out), pushing consumers to act quickly, often without thinking. These tactics bypass rational decision-making, luring buyers into transactions they might later regret. They use various such tactics to prime us to spend throughout the flash sales period on repeat. That is when persuasion turns to manipulation.

Challenges and the Way Ahead:

While India is one of the few countries regulating such dark patterns, they remain hard to enforce. As Karthika Rajmohan from the Internet Freedom Foundation explains at our recent event, consumer rights and data protection laws operate in silos, making it difficult to address issues that overlap both. Companies, meanwhile, have little incentive to comply with these guidelines when the profits are so lucrative. Aishani Rai from the Aapti Institute suggests that only collaborative efforts between regulators, researchers, and civil society can address these problems.

But until this happens, we all continue to fall for the cheese in the trap, thinking we have scored a “deal” while the platforms laugh all the way to the bank.

Round Ups

Economics for Everyday Decisions

Why study economics?

The vast majority of individuals view it as a means to an end, either financial security or access to a wide range of electives. However, Giorgio Castiglia, a PhD student at George Mason University, challenges this notion, arguing that economics encompasses more than just policies and broad-based theories. In fact, it can serve as a valuable tool for making more informed decisions in daily life. He recommends Bryan Caplan’s Self-Help is Like a Vaccine for practical tips. Although it might not resonate with everyone, it presents a fresh viewpoint on how economics can break free from its traditional textbook image. Reading this piece gave me an idea about why we Indians seem to be culturally proficient at economics, but I will save that for another time. For now, it's a challenge to turn big, theoretical ideas into tools for the masses. And as James Marell famously wrote, we are all lost in the translations.

Read the original article here.

India’s Changing Spending Habits

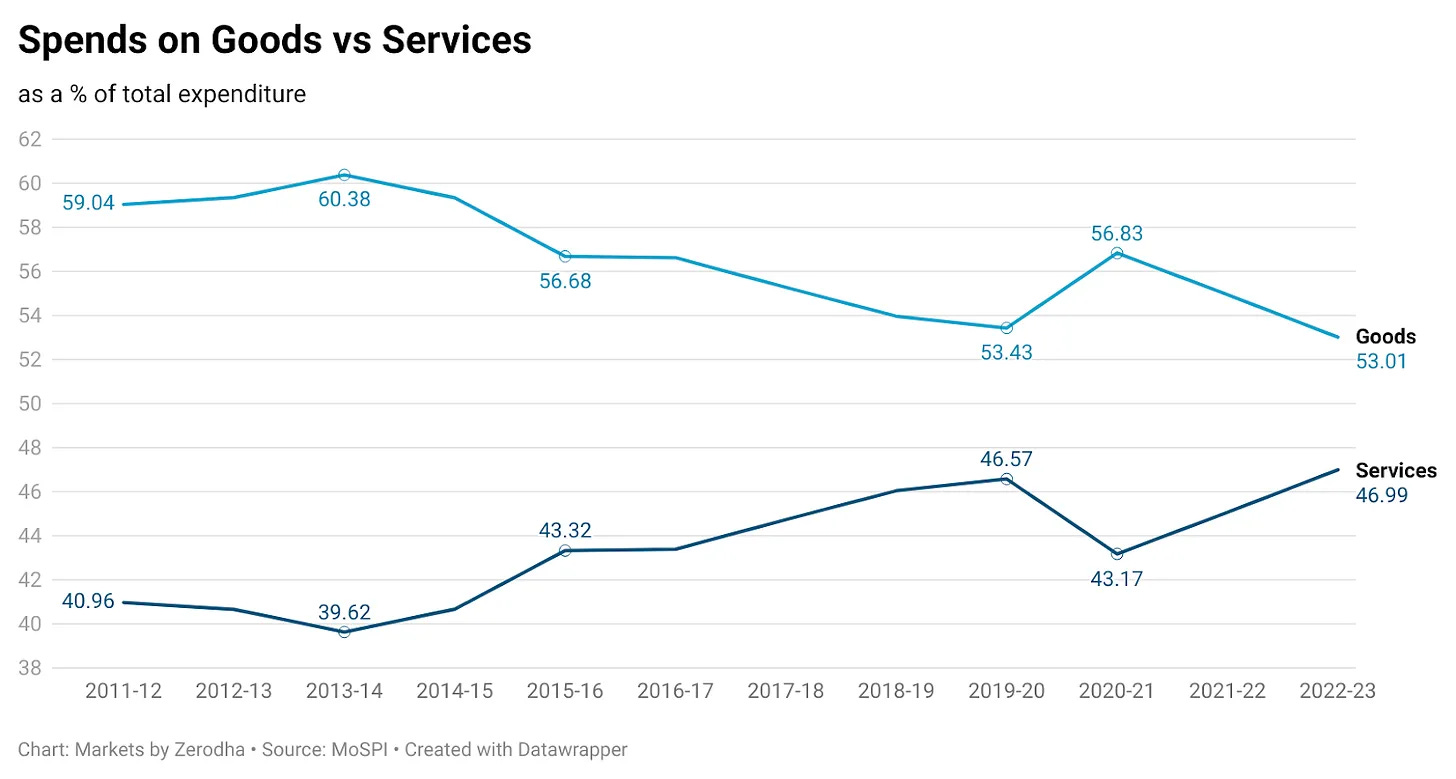

Have you noticed how your spending has evolved over the last decade? You're not alone. A dive into MoSPI data (2012–2023) shows surprising trends in India's consumption patterns. While Engel’s Law suggests rising incomes should reduce food’s share in budgets, Indian households still allocate 28-32% to food.

Health-conscious spending is rising—protein intake is up, sugar down—but economic disparities blur the picture. Post-COVID, insurance spending doubled, reflecting heightened awareness. Meanwhile, services like education and healthcare now dominate over material goods.

Read more on The Daily Brief. All the data-related images are from this newsletter.

Market for Adulterated Food

I have lately been watching movies like 11 Fake Foods, which show how often the convenience and pleasure we take for granted come at the expense. Consider this: most olive oil, honey, ghee, or even wasabi are fake because production can’t match demand. Yet, shelves stay full. The gap is filled through adulteration, not because we demand fakes, but due to imperfect information. Advertising, coupled with weak regulatory checks, creates a fertile ground for deception—classic market failure. Skewed incentives drive industries to cut corners to meet demand. The market for adulteration, meantime, depends on our readiness to put convenience and cost above authenticity. When such products flood the market, our capacity to tell real from phoney gets compromised. Our tastes change with time; we pay for the concept of honey, olive oil, or ghee rather than necessarily its authenticity. It’s a phenomenon mirrored across industries, from fast fashion to luxury goods, where cheap replicas dominate.

So, this sale season, are we buying the real thing or merely the illusion of it?

Maggi-c in the Mountains

In India, no trip to the mountains is complete without a steaming bowl of Maggi. But Maggi’s journey to becoming a household name wasn’t by luck—it is a case for behavioural economics. By offering free samples in schools, Maggi leveraged pester power, making kids the drivers of demand. The ₹5 "chotu Maggi" leveraged price elasticity and made it affordable for rural and low-income families. Clever ads showed Maggi as the go-to meal for busy days or cozy nights, while Nestlé’s strong distribution ensured it was available everywhere, from big cities to remote villages. The secret? Solve a problem, make it affordable, and be everywhere.

💡

Written by Farheen