IP Wave This Weekend: To nudge or to boost?

Imagine you are trying to predict the next US president.

You don't need to analyse debates or poll numbers; you just need to ask 13 questions.

That’s exactly what political historian Allan Lichtman did in 1981. His model was built on "keys" like the economy and wins in foreign policy. It had nothing to do with people or scandals. Instead, it focused on things that were factual. The rival would win if six or more of these keys turned against the party in power. It was amazing how simple it was. Lichtman's model wasn't super complicated; it took chaos and turned it into order. Surprisingly, it has been right about almost every election since then except 3 (2 of which were Trump elections).

At TAPMI - Max Planck Institute Winter School on Boosting Informed Decisions , we explored how simple, transparent tools can help people make better decisions, even in complex situations. I walked in expecting a dry lecture on theories and data, but what I got was a crash course in the messy, beautiful complexity of human decision-making.

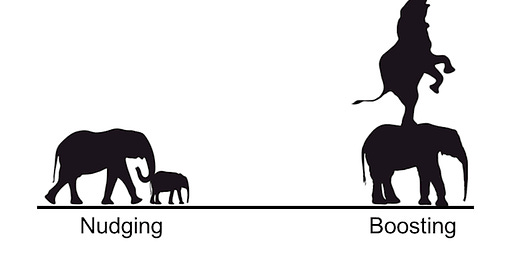

Changing behaviour, it turns out, is less about clever strategies and more about understanding the quirks and biases that drive us. It's a lesson that's both empowering and humbling. We can't simply "nudge" people into making better decisions; instead, we need to give them the skills to decide for themselves. This is what's known as "boosting," and it's a concept that has far-reaching implications.

Take the Dutch Reach, for example. It's a simple habit that drivers can adopt to prevent dooring cyclists. By using their far hand to open the car door, they automatically check their blind spot. It's a skill, not a rule, and one that can be applied anywhere. This is the power of boosting: it gives people the tools to make better decisions, rather than simply following a set of rules.

But there's another challenge that we face when it comes to decision-making: the description-experience gap. When we read about something, we process it differently than when we experience it ourselves. This is why people often trust their own observations more than general information. It's a gap that can have serious consequences, particularly when it comes to risk assessment. But what if we could close this gap? What if we could create models that allow people to "experience" the results of their actions rather than just reading about them?

One way to do this is through the use of virtual reality scenarios, such as those that show the long-term effects of smoking. By allowing people to "experience" the consequences of their actions, we can make risks seem more real and decisions more informed. It's a powerful tool, and one that has the potential to transform the way we make decisions.

But complexity can be overwhelming, and that's where simplicity comes in. Simple models, such as fast-and-frugal trees (FFTs), can be incredibly effective in complex decision-making environments. Unlike "black box" algorithms, FFTs have a clear, step-by-step process that makes them transparent and trustworthy. They've been used in high-stakes scenarios, such as triaging disaster victims or guiding military operations, and their strength lies in their simplicity. We explored how LLMs can use these to make more transparent decision-making.

Overall, as I reflect on my experience at the Winter School, I'm left with more questions than answers.

Are we truly irrational, or are we just adapting to imperfect systems? If boosting skills and leveraging simplicity can transform decisions, how much further could we go by aligning environments with human strengths? How do we close the gap between what we know and what we experience? And most importantly, what could we achieve if we started viewing human decision-making as a strength to build on rather than a flaw to fix?

The answer, much like the question, remains unclear.

Round Ups

How quick commerce is rewiring your brain

India’s quick commerce revolution is reshaping consumer behavior and raising mental health concerns. Instant delivery apps like Blinkit and Zepto, initially focused on essentials, now deliver everything from ice cream to smartphones within minutes, creating powerful dopamine loops similar to social media addiction. This instant gratification eliminates the reflection time that might curb impulsive decisions, leaving vulnerable groups at risk of financial instability. While quick commerce platforms are set to grow at 70% annually over the next five years, the broader implications for consumer psychology and societal well-being remain to be fully understood.

Read more

10-Minute Dopamine Rush: How quick commerce is rewiring your brain

Why Do Some of Us Crave Self-Insight?

Some people have a strong desire to understand themselves, but the path to self-knowledge is rarely simple. Research shows that while younger, curious individuals often pursue self-awareness, their motivation doesn’t always lead to accurate insights. Factors like biased feedback and the self-enhancement motive can distort reality, but mindfulness offers a way to foster honest, non-judgemental self-reflection. Embracing both strengths and flaws can lead to a more authentic understanding of who we are. The journey isn’t easy, but it’s worth the effort.

Read more:

What makes some of us crave self-insight more than others? | Psyche Ideas

Who Owns the Moon’s Airwaves?

Private companies are increasingly filing claims for radio spectrum on the Moon, signaling the rise of a lunar economy. FT research reveals over 50 spectrum applications since 2010, with commercial filings surpassing those of governments for the first time in 2024. This marks a critical shift as companies like Intuitive Machines and Firefly Aerospace plan Moon landings and satellite systems to relay data. Analysts predict $151bn in lunar mission revenues by 2033, primarily from government contracts but with growing commercial interests. The race for lunar airwaves highlights the need for updated spectrum regulations to manage this expanding frontier.

Read more:

The race to claim the Moon’s airwaves

Can Governments Learn From Their Mistakes?

The democratic world seems caught in a feedback loop of policy errors, desperate gambles, and more policy errors. But what might a better approach look like? Donald T. Campbell’s 1971 lecture, Methods for the Experimenting Society, offers a blueprint. Campbell advocated for an active, honest, and nimble society—one that rigorously tests solutions to persistent problems, evaluates them honestly, and moves on when they don’t work. Campbell’s vision isn’t just about evidence-based policy; it’s about embracing curiosity, humility, and practical action. In polarized times, these virtues feel rare. But as Campbell said, “We do not have such a society today.” Perhaps tomorrow.

Read more:

Why are governments so bad at problem solving?

💡

Contribution by Farheen